|

from the archives... What a worthy translation by David Jack. The second in his translation series, this latest 2018 edition of Castle Warlock provides the complete original Scots text side by side with English. In his introduction Jack writes, “Many people know MacDonald chiefly as a writer of fantasies, and indeed within the story of Castle Warlock are elements of the supernatural worthily handled by the master.” And I agree. George MacDonald’s novels aren’t bound to plot as other fiction works of the 19th century are. Rather, MacDonald is bound to the poetic truth he must tell through his characters and the places they live. Treasure this as a slow read with beautiful waysides, not as a plot-driven romp. MacDonald narrates, “I think we shall come at length to feel all places, as all times and all spaces, venerable, because they are the outcome of the eternal nature and the eternal thought." When we have God, all is holy, and we are at home. The sense of belonging and the theme of fatherhood are constants. But they are things that must be found or realized. This search is evident in young Cosmo Warlock as he matures under a wise and humble father through the length of the book. No honest heart indeed could be near Cosmo long and not love him—for the one reason that humanity was in him so largely developed. The lives and stories of Joan, Aggie, and Grizzie join Cosmo’s as we slowly and certainly come to love them all. They are the stories of friends as MacDonald consistently teaches us of God’s faithfulness. Though I struggled with Cosmo’s lack of discernment when the doctor entreats him about Joan, I chalk it up to the struggle of youth and experience as MacDonald may have intended. And finally, I do admit to crying upon reading MacDonald’s poem postlude. Such beauty in the meaning of shadow and light, and how much more in God’s light revealed through MacDonald’s characters.

For information on David Jack's brave work of translating all twelve of MacDonald's Scots novels, read more at The Works of George MacDonald and enjoy a listen here.

2 Comments

What if my imagination was stunted, having never really grown? I admit I haven’t considered this idea before. Call me naïve, but I supposed everyone had an active imagination whether it was sluggish or bustling. When I recently read David Beckmann’s account of C.S. Lewis and the London evacuees in Life with the Professor: The True Story Behind the Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, I realized I had forgotten much of Lewis’s experiences during World War II when a number of school-age girls stayed with him, his brother Warnie, and their household help at the Kilns. Evacuees stayed for a few months or a few years while attending school nearby. Lewis quickly realized he and his brother could be positive influences on the children. Yet both men were also quick to admit they had had “little experience” with children in general. Lewis soon found he was a father figure, a homework helper, and chore enthusiast. He also was adept at spoiling the girls. Bypassing his housekeeper Mrs. Moore, he slipped snacks and treats to them regularly. But Lewis noted one thing was missing in the girls’ development—an apparent lack of imagination. It was as if the imagination muscle had atrophied. If he told a story on a long walk or at bedtime, the girls hardly knew what to do other than listen. Beckmann is certain Lewis began work on the Narnia Chronicles at this time, as early as 1939. Cultivating the imagination of children was simply one more motivation in his fiction journey. Beckmann writes, By the time the war was over, Lewis had a true, loving appreciation for the young and a compassionate concern that they learn to love the imaginary." Not all of us as children could craft the Boxen stories as Jack and Warnie did nor as the Brontë siblings did with the kingdoms of Angria, Gondal, and Glass Town. Maybe some would say our imaginations are lesser in comparison to these literary greats. Maybe so, but I'm not discouraged. Our imaginations are not extinct.

Beckmann’s short and relatable account quickened a train of thoughts for me. I wondered what role war and separation from family played in stifling the imagination of those girls. What about now? What other stressors inhibit creativity in the young? What about the old and all of us in between? Is it possible to kill the imagination entirely? Can we stir our own imagination? Join me in my ponderings this January. Share a comment or two below. “I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it.” —C.S. Lewis I can’t explain it as well as I’d like, but there’s something to George MacDonald’s preachy style. As a teenager, I read voraciously and whipped through a number of his romances such as The Seaboard Parish (1869) and The Fisherman’s Lady (1875). In each story, a prominent character is in need of a rescue, and in a predictable pattern, MacDonald provides a devout Christian who could guide and lead the needy to Christ. Simple conflicts, happy endings, nice and neat. Yet these are only one type of novel he wrote. The fairy and fable of his early years feature deeper, even darker thoughts. Consider Phantastes (1858). Here, young Anodos, meaning pathless in Greek, discovers an atypical fairy world, a place of goodness and darkness. The inexperienced Anodos doesn’t always know who to believe among the world of fairies, trees, and creatures, and most alarmingly, he unearths his own shadow, a being that is himself and yet wholly evil. After many adventures by fable’s end, Anodos reawakens in the real world and finds he has been asleep for twenty-one days. This type of fantasy along with MacDonald’s children’s stories and poems is only one small part of his writings though. Having been a Congregational minister for a time, MacDonald can’t seem to keep himself from sermonizing, let alone moralizing, in his stories. So recently I picked up a piece of his I hadn’t read before, Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood (1866). Our story begins with the honest and friendly greeting of Harry Walton, a new vicar in a rural parish harmlessly called Marshmallows. The story is replete with stereotypical characters such as the rich old widow manipulating others through her position, the old geezer working the local grain mill, the young working-class couple separated by a gruff father, and so on. What’s unique is MacDonald’s perspective. Young Walton is ever the narrator and describes what he sees: “Why did I not use to see such people about me before?” He recognizes that he is learning to truly see each parishioner as they are, and his ideals are clear. He is driven (or is it inspired?) to make God real to the people in his charge: a man must be partaker of the Divine nature; that for a man’s work to be done thoroughly, God must come and do it first himself; that to help men, He must be what He is—man in God, God in man—visibly before their eyes, or to the hearing of their ears. So much I saw. Through Walton’s eyes and ears, we see his encounters and hear his sermons. We see his sincere desires and his need to bring people together, even if he must solve the mysteries of people themselves. He is a winning protagonist, even if pedantic in times.

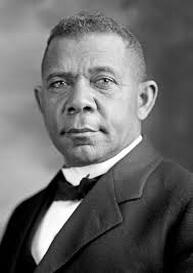

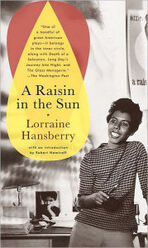

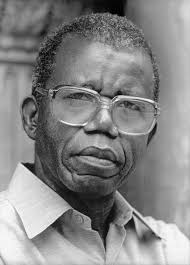

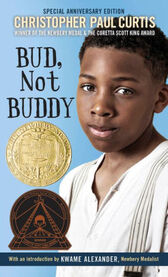

Personally, I enjoyed hearing the voices of the Victorian age, whether the Spenserian carols at the vicar’s Christmas party or the pulpit pounders straight from MacDonald himself. Unlike other MacDonald novels, Scottish brogue and dialect are hugely absent since our narrator is a cultured man, all the easier for his audience to enjoy the style and theology that is MacDonald’s. Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood is available in several volumes now as a reprint or digitized for public use at projectgutenberg.com. The Wade Center at Wheaton College and the George MacDonald Society websites provide a delightful array of resources and texts. Librivox also features 19 hours of MacDonald’s Unspoken Sermons. Spanning generations and political views, the authors I teach here have influenced how I see people, how I see my own students, and hopefully how we all see the world we live in.  1. Booker T. Washington If you read my blog, you know I’m an ardent fan of Washington and his words. [See An Educator’s Devotion and Booker T. Washington’s Compromise.] When I read his Character Training (1902) in January this year, I was inspired to be more intentional in laying excellence as a standard in my classrooms. I’ve continued to read more of his works and biographies by others, including the singular The Negro in the South lectures with W. E. B. Du Bois. It's interesting to see the two men juxtaposed. Even if you've never read these men before, Washington is naturally more positive in these lectures while Du Bois's deep sense of injustice permeates his words.  2. Lorraine Hansberry Just as Washington believed hard work and perseverance were noble efforts, Hansberry depicted a different reality in the 1950s, the limitation of the American Dream for black Americans. I know it’s not her only work, but her play A Raisin in the Sun (1957) is such a living picture. She writes to her mother, “It is a play that tells the truth about people. But above all, that we have among our miserable and downtrodden ranks people who are the very essence of human dignity.” It is the essence of a merciful humanism, a good kind, that stirs understanding in the middle of activism.  3. Chinua Achebe Like Hansberry, Achebe was published by the age of 28. I first read Achebe in college under the tutelage of a visiting professor from Nigeria. More than the class discussions about Things Fall Apart (1958), I remember the sense of my cultural ignorance. Yes, suffering, pride, and injustice are human frailties, but more than that, a native son can criticize his own country for allowing Western values to compete with traditional African culture. I also read his second novel No Longer at Ease (1960) and include my reflections here in Reading Binges. It very much reminded me of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.  4. Christopher Paul Curtis I first read Bud, Not Buddy (2000) with my oldest son when he was in third grade. Bud, a ten-year-old African American boy, runs away from his abusive foster family in Flint, Michigan. He embarks on a journey to find his father, enduring the fears and horrors of the Great Depression. Written in a strong, compelling voice, Bud, Not Buddy beautifully evokes what life was like for African Americans, especially musicians, in Michigan during the Depression. Since then, my family was captured by Curtis’s historical fiction, having read The Watsons Go To Birmingham and Elijah of Buxton. I continue to recommend Curtis to families looking for compelling historical reads.  5. Harriet Ann Jacobs At the recommendation of Karen Swallow Prior, I finally read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) two years ago. Not only had I never heard of the account, but my students hadn’t either. I now include excerpts from Jacobs after I teach Washington's Up from Slavery. Jacobs addresses her autobiography to white Northern women who fail to comprehend the evils of slavery. Published in 1861, it is a harrowing account of hiding for seven years before being reunited with her children in New York. After the Civil War, Jacobs traveled to Union-occupied parts of the South together with her daughter to organize help and begin two schools for fugitive and freed slaves. Her book was well-received in America and England. Experience humbles us. So does sin. In My Divine Comedy: A Mother’s Homeschooling Journey, Missy Andrews not only presents an educator’s memoir but also a spiritual trek, one reminiscent of Petrarch’s “Ascent of Mount Ventoux.” Andrews details the failures of relying on ourselves as parents and educators. Those failures spoke to me as a mother and as a teacher because she calls us to remember that motherhood and home education are “fruitful work.” But not before reminding us that our students might be performance-driven because we have modeled it for them first. It is the age-old problem of confusing what we do with who we are. Our work as educators or as parents is not our identity nor should our identity be based on our performance checklists, or testing, or following the latest and greatest curriculums. If we do not see that we are imperfect, that our motives and our ideals are impure, we can be guilty of creating an idol out of education itself. Andrews asks us if we’ve mistaken “the good gifts of God for the Giver.” And that’s the point. What is education really? Andrews has a wonderful way of describing what it is by what it isn’t. I was captured by her comments on what she called “the identity race” that we see in every type of schooling—public, private, home, or co-op. We can mistakenly train children and teens with questions like “What are you good at?” rather than “Who are you really?” When we equate schooling with performance and doing, we mislead our students and cause them to ask, “Is anything good enough ever?” Here, she poignantly cites the account of the prodigal son and his brother in Luke 15. In this instance, both boys saw themselves as doers, employees, rather than as sons of a loving father. Andrews leads us through scripture and literature to show us the truth of Proverbs 29:25 — the fear of man is a snare because we become man-pleasers. She is clear. We will never know it all and neither will our children or our students. They need to know this from the beginning. True education familiarizes a child with the stuff of goodness, truth, and beauty in order to equip him with eyes to see his true condition, the shortfall between the ideal and the real. This self-awareness has the potential to awaken humility and prime the soul for an encounter with the sole source of goodness, God Himself.” Andrews’ memoir is not about perfect solutions in education or becoming the ideal homeschooling parent. Rather, it’s about a shift in perspective, a humbling awareness of God’s abundant grace that makes us fit for good work.

Read more Book Reviews on classic and contemporary novels. LIKE MANY READERS during this time of pandemia, my attention comes and goes with the needs of my household. All the classics I want to read or reread are simply standing dusty on the bookshelves. But I do find myself drawn most to fables and fairytales, well because, short reads do count. Short reads are more approachable because of their length but that doesn’t mean they lack depth, beauty, or truth. And many of these are suitable for family reads and discussions:

I read so much this summer that it was hard to choose what to include this year. And I almost added a new category titled BOOKS I HATED but thought that might be too much! Hint: They are excoriated (ahem! listed) on my Goodreads account. POPULAR READS.

I have many, many more books to read (and a few to write), but do share your own favorite summer reads in the comments below. I'd love to hear what brought you delight or simply got you thinking! HAVING GROWN UP IN MISSISSIPPI, I have a weakness for Southern fiction. My curiosity was especially piqued by a friend’s gift and this Southern claim. I do confess to admiring many of John Grisham’s novels, particularly Sycamore Row, but I I rarely read a bestseller unless a better-read friend attempts it first. I shun New York Times’ bestseller lists simply because they are popular. Forget the press and the hubbub. Case in point. I made the mistake of reading Gone Girl a few years ago and have always regretted the hours I lost. I found I intensely dislike amoral stories without one character to savor or cheer for. Thankfully Delia Owens’s Kya Clark is not that character, though she appears a pitiful orphan in every way. How forlorn to hear young Kya’s thoughts—“What she wondered was why no one took her with them.” Yet this read is more than character-driven. In Where the Crawdads Sing, Owens steeps her readers in a thoroughly engaging marshland setting. In fact, I would go so far as to compare her land to a living character much like Willa Cather does in her immigrant novels. The land is ripe with paradox—safe yet dangerous, shining yet muddy, life amid decay. Like Cather, Owens’s language fills us with every sensation and plants us firmly in Kya’s world of loss and hope. The land indeed nurtures her into and through her adult life with a “yearning to reach out yonder.” In her younger years, nature is a place of solace, a companion. But once her heart is awakened to human love and to the real relationship of years, creation cannot fill the void in the human heart—-- But just as her collection grew, so did her loneliness. A pain as large as her heart lived in her chest. Nothing eased it. Not the gulls, not a splendid sunset, not the rarest of shells.” And there is a void. More than a century before, Cather writes of this too. Within O Pioneers!, the land is characterized more by its strength than by its vastness. Like a human personality, it can be overbearing or supportive. Alexandra Bergson understood this. She too was intimidated at first as “the land wanted to be left alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar kind of savage beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness,” but as decades passed, the land appears an empathic friend as it “responds in kind.” More than personified, the land becomes a rounded character in full relationship with man.

Like Alexandra Bergson, Kya possesses a faith in the land that others lack. The land is wholly human to her in relationship. And, if she has a faith, then it is no wonder that creation responds to her and reveals its treasures. It is there that she finds friendship with the marsh’s creatures, safety from prying eyes, relationship with her first love Tate, inspiration for the work of preserving nature in art. More than eco-fiction, this novel doesn't preach of preserving the marshland, at least not overwhelmingly like a smarmy salesman. The story is one of relationship. Where the land could have been seen as a trap that limits, it is ultimately a place of rescue for Kya. Photo by Timothy L Brock on Unsplash  What a worthy translation by David Jack. The second in his translation series, this latest 2018 edition of Castle Warlock provides the complete original Scots text side by side with English. In his introduction Jack writes, “Many people know MacDonald chiefly as a writer of fantasies, and indeed within the story of Castle Warlock are elements of the supernatural worthily handled by the master.” And I agree. George MacDonald’s novels aren’t bound to plot as other fiction works of the 19th century are. Rather, MacDonald is bound to the poetic truth he must tell through his characters and the places they live. Treasure this as a slow read with beautiful waysides, not as a plot-driven romp. MacDonald narrates, “I think we shall come at length to feel all places, as all times and all spaces, venerable, because they are the outcome of the eternal nature and the eternal thought. When we have God, all is holy, and we are at home. The sense of belonging and the theme of fatherhood are constants. But they are things that must be found or realized. This search is evident in young Cosmo Warlock as he matures under a wise and humble father through the length of the book. No honest heart indeed could be near Cosmo long and not love him—for the one reason that humanity was in him so largely developed. The lives and stories of Joan, Aggie, and Grizzie join Cosmo’s as we slowly and certainly come to love them all. They are the stories of friends as MacDonald consistently teaches us of God’s faithfulness. Though I struggled with Cosmo’s lack of discernment when the doctor entreats him about Joan, I chalk it up to the struggle of youth and experience as MacDonald may have intended. And finally, I do admit to crying upon reading MacDonald’s poem postlude. Such beauty in the meaning of shadow and light, and how much more in God’s light revealed through MacDonald’s characters.

For information on David Jack's brave work of translating all twelve of MacDonald's Scots novels, read more at The Works of George MacDonald and enjoy a listen here. IT'S TRUE I came to Leif Enger’s novel late, almost two decades after it was published, but it resonated with me in its prose, its simplicity, its relationships. Like Reuben who always struggled with asthma, I caught my breath as I read. Life came after a moment of suspense. Hope returned. This struggling motherless family in 1963 North Dakota shared a beautiful, imperfect life. Through the young eyes of Reuben, however, life is different and his father, his tellings, his relationship with God throughout the story, are essential to the reality Reuben believes. His father Jeremiah Land is the everyday hero who loves well. Reuben witnessed and heard his father pray and speak to God in realness, and it tainted, yes tainted, everything the boy saw and experienced from the miracle of life when his lungs refused to breathe at birth to his father walking on water or to protecting a son, the miracle is there. It is a living, breathing thing. And I still can’t entirely grasp how Enger did it. It had to have been something he lived to inhabit the story so. Perhaps it was the element of sacrifice, that permanent expression, that made love real. We see it in each relationship—Reuben and his older brother Davy, Reuben and his sister Swede and the stories she creates, and especially Reuben with his father.

Through his physical suffering that long winter, Reuben wonders, “Shouldn’t that be the last thing you release: the hope that the Lord God, touched in His heart by your particular impasse among all others, will reach down and do that work none else can accomplish—straighten the twist, clear the oozing sore, open the lungs? Who knew better than I that such holy stuff occurs?” But the miracle didn’t happen in that moment of need. It waited for the greatest need. By their nature, miracles are undefinable. If they were concrete things, solid words and such, then the word would lose its potency. Not just anything can be a miracle. Reuben’s life is real, not contrived, and life is indeed a struggle except for those miracle moments that breathe more life into us. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed