|

I enjoyed a unique phone call recently. One of my former students reached out for help with a long essay. As a hopeful history major, Eric wanted to submit a college application essay on a historical subject he loved—the French Revolution. He had narrowed the topic to the role of Royalist journalists and had completed all of the research, including some amazing digitized letters and propaganda from that time period. Unfortunately, the essay had practically become a list of quotes and sources and key figures. Some connections among them had been made, but it wasn’t coherent. Yet. We circled back to his premise, and I asked, “What is your point? What are you leading us to understand?” That helped a little bit, but Eric said he needed more time to think about it. So of course I asked him to revise it further, and he immediately asked, “What does that word mean?” Good question. From Latin and French roots, revise means to look at or look over again. It sounds horribly simple: By the 1590s, revise came to mean "to look over again with intent to improve or amend."* But that doesn’t help the student know what to do. They understand by context that they must make corrections. These are the concrete elements, the checklist, the things the teacher may have noted like “add a transition phrase here” or “choose a stronger verb” or “check for commas.” This is editing, not rewriting or revising. But Eric had moved beyond concrete editing already. As teachers, we have to remember that we are both readers and writers. If we instruct in writing, it’s because we read first. In God in the Dock, C.S. Lewis reminds us that “The reader, we must remember, does not start by knowing what we mean. If our words are ambiguous, our meaning will escape him. I sometimes think that writing is like driving sheep down a road. If there is any gate open to the left or the right, the reader will most certainly go into it.” And that compelled me to ask Eric a few questions: How can you make your writing more clear? Is there a sentence or thought that obscures or leads you away from what you really mean to say? If you were an editor of a historical journal, what would you cut as excess?” In this instance, it was a fruitful exercise. He immediately cut several “interesting” facts that did not lead to his real point—the Royalists believed revolution was sin because they were preserving the semblance of Jesus Christ, King Louis XVI. Eric eliminated four sentences in four pages. He told me it was easier to see once I mentioned that sentences can lead away as well as lead us to the premise. It may not seem like a lot, but by removing them, he could more easily see what needed to be connected.

I hesitate to use the phrase “big picture,” yet I would ask if we can see the essay as a whole. Can we see our way in the forest through the leaves of words or has the path been obscured? Before, fascinating tidbits led Eric into the weeds and fields beside the path. By eliminating what led him away, he gained the path again. Each fact, each quote, each sentence connected his journey along the path of the essay. And seeing might be the point of revision, to re-vision our thoughts. *Online Etymology Dictionary

0 Comments

I received a rejection last week. From one year ago. An agent whose work I admire had requested a full manuscript for my middle grade novel. I enjoyed the read – you’ve got a great voice here, and I really liked the concept, but in the end, I just didn’t fall enough in love to be able to offer representation.” For those in the writing trenches, you’ll recognize the wording of a standardized rejection. It’s neither encouraging nor discouraging. From an agent, it could mean “Your story is not for me” or they (or their assistant) really weren’t captured enough to read it, let alone provide feedback.

Rejection is an odd thing for me as a literature teacher because I delight in words. Reading, absorbing, experiencing, teaching, analyzing, writing. As a teacher, I hope to never suck the joy out of the reading experience for my students. I certainly endured more than one class in high school and college that did that well. Analyze. Pull the story apart. Pick it to death. Put it back together. Mash it into the meaning the teacher wants. Textbooks can often be structured that way too. I wonder if many are built for overworked teachers, to make their lives easier. They might include commentary on a theme, different levels of discussion questions, and ideas for essays. Sometimes I’d rather they didn’t. It can be too prescriptive because the textbook authors are giving you their meaning. On the surface, it’s like saying that teachers and students alike are incapable of thinking through these things. It’s practically miraculous that any student comes out of that system having enjoyed the story still. And that’s the odd parallel. In writing fiction, I have to be aware of all of the parts, like ingredients in a recipe. I know what I’m making, but every separate thing must come together. I have to be intentional. I have to be aware of word choice, lexile, backstory, setting, point of view, tone, characters’ needs and wants, the arc of each character, the arc of the plot, scene structure—so many things. It’s the opposite of how I read and how I teach reading and writing. I realize now that I most appreciate a holistic approach. I do think all of the parts come together as a whole, a synchronicity of sorts. For some writers it comes naturally. For others, like me, it comes through labor and training, especially through the imitation of others. And that gives me every hope that as I teach my students parts of the whole, I can do it in a way that doesn’t suck the joy out of the reading experience. We don’t have to notice absolutely every thing in a story to enjoy it. As I lead a class, I can model that. I can choose to emphasize perhaps two or three things an author has constructed. As I am aware, even hyper aware of what an author has done in the story structure, I am able to encourage my students to appreciate the grand design.  I love a good mess. Over the past week, two handymen have been working on our house, replacing rotted siding and a handful of windows. They have touched almost every room in our house for one reason or another and tend to leave funny little bits behind. As I’m writing this at my bedroom desk, I can see a small plastic package of unopened screws left on my desk. If I walk into my bathroom, I find a new package of long brass wood screws. If I toodle over to my husband’s office, I can see a red-handled wood chisel sitting high up on an upper window sill. Every room has something left behind, or, if I look at it in another way, a tool or supply for equipping us in our repairs. Perhaps it’s more than home repairs because repairs make me think of one book I’ve slowly ingested this summer--Madeline L’Engle’s Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art (1980). You see, in the writing game, I fight discouragement regularly. I fight doubt, purpose, all those things. L’Engle does not deny the negatives and speaks candidly about her “decade of failure” where doubt and guilt consumed her with “bitter lessons” in her writing journey. Her compilation of thoughts on the process of writing amid reflections on her spiritual life has become a nourishing devotional to me in the summer season. We think because we have words, not the other way around. The more words we have, the better able we are to think conceptually." L’Engle consciously turns her focus to how God works through us. “But we also need to be reminded in this do-it-yourself age that it is indeed God who made us, and not we ourselves. We are human and humble and of the earth, and we cannot create until we acknowledge our createdness.” She explores many tangents along the way but always returns to “An artist is a nourisher and a creator who knows that during the act of creation there is collaboration. We do not create alone.” I’ve copied many of these quotes in my writing journal this summer, writing them down over and over. It’s like the life of L’Engle’s words have become my cheerleader, bringing me back to center. When I am constantly running there is no time for being. When there is no time for being there is no time for listening.” And I do want to listen as I read and write. I don't want writing to become my busyness.

To repair is to mend and put back in order. But its Latin root parare means to make ready, to prepare. I trust that I am “making ready” again, preparing for the life where my words fit in the homes God has for them. OVER A YEAR AGO, I read Don King’s Out of My Bone: The Letters of Joy Davidman. I was struck by how quickly I felt Joy’s presence and personality in her correspondence with her sons, ex-husband, and husband-to-be, C.S. Lewis. Brash, opinionated, desperate, loving. Spanning years, these letters revealed more than a screen could. I felt who she was through her words. As one of my tutorial students and I finished discussing Pride and Prejudice this week, I was reminded of this same crystal realism. He had never read a book where letters were used so much, and he was surprised at how effective they were in fiction. As our conversation meandered, we gradually spoke of one of the most significant letters, one that Austen must have crafted with great care. As readers, we have joined Elizabeth in her misinterpretation of several characters, including Darcy. In Volume Two, Elizabeth has just rejected Darcy’s proposal of marriage and accused him of malice towards her sister Jane and towards Wickham. He then graciously extracts himself from her rudeness and sends her the longest letter of explanation the next day. It is a pivotal moment for Elizabeth and for Austen’s readers. As Elizabeth reads, we hear Darcy’s truth through his voice. In person, he speaks little in contrast to others, but here, in a letter, he is vividly present. His manners, his balance of diffidence and kindness are all revealed in his measured choice of words. We know him. I know him, and the feel of it astounds me still. But as in real life, letters can carry a sense of who a person is or was. I realize letters in literature are not new. But as in real life, letters can carry a sense of who a person is or was. Perhaps it is the deliberate time and care they take to write. My writer friend Michael De Sapio says, “It is an act every part of which expresses care, attention, and deliberate intent. It costs more, in every sense...writing a letter forces you to filter your information and set down the essential and significant. It is a true act of creation, with nothing random about it.” (Why Letter-Writing Is Essential to the Good Life)

To me, the personal creative act must be what reveals our essence, our personality in a selection of words. Whether fiction or fact, letter writing can express who we are. So how about it? I noticed lots of articles and features on writing letters at the beginning of the pandemic. I didn’t write much by hand, did you? Do you hope to? Has writing letters or reading them enriched you? Comment below or email me back. I’d love to hear more. Perhaps the word inspiration has become trite. Whether I'm writing fiction or nonfiction, I've been asked more than once if I ever "feel" inspired to write. I know it's a standard author-type question, but I don't quite believe in the idea of a grand light-bulb moment or a guiding Muse. I do, however, often read something that gives me an idea or image. That definition of inspire I do agree with--to produce or arouse a feeling, thought, etc. Two years ago, I was trying to choose a John Donne poem to teach to my high school juniors. And, as often happens, I kept reading because I was enjoying reading Donne for the delight of simply reading poetry much like C.S. Lewis's idea of "receiving" versus "using" the poems we read. In An Experiment in Criticism, Lewis also mentions how we delight in the stir of our imaginations. When I encountered Donne's Holy Sonnet V [below], I had a glimmer of an idea. In the moment, I wasn't stirred by his purpose of calling us to repentance. No, I was captured by the image of new spheres and new lands as Donne cried out for the eternal hope of seeing them. I am a little world? The angelic juxtaposed with black sin? New spheres? New lands? It was then I sensed it. I call it a compelling. What new world could I picture? What could I write of? These were the moments that led me to begin writing fiction for the first time, the completed middle-grade fantasy novel I am querying today. I am a little world made cunningly *My favorite Donne collection remains the Everyman's Library Pocket Poets Series because...well, who doesn't like a pocket-size book of poetry?

TEACHING MY STUDENTS how to improve their own writing is no easy task. I emphasize content and typically focus on one to two stylistic elements per assignment. At the beginning of the school year, I quickly noticed that my seniors were overfond of the verb “use” in most any casual or formal writing assignment. We quickly built a synonym base for the word on the whiteboard and discussed connotations. For several months, I had them search and highlight the word, allowing for a single use. As I worked on my novel these past months, my editor had to repeatedly teach me how to balance my use of active and passive voice in both dialogue and narration. Repeatedly. It took a number of attempts for my brain to get it. And practice was very much a part of the process. My point is that it often takes mini-lessons like these as we each take steps in our writing or even speaking. And that is when writing style guides can be such a help. But forget writing classics like Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. The concept of spelling out rules with writing examples was tackled well before the 20th century. Think of Aristotle’s Poetics in 4th century BC. Though he focuses on drama and epic, he does address the use of language and a playwright’s diction. But I would be remiss if I didn’t also consider a short but splendid stylebook of the first century, one that considers the written and the spoken word. More than our contemporary guides, Cassius Longinus explores the motive of the writer. Why is he writing? What is his end? But more importantly, can we attain sublimity of language? Are we capable of learning it? A lofty passage does not convince the reason of the reader, but takes him out of himself. That which is admirable ever confounds our judgment, and eclipses that which is merely reasonable or agreeable. To believe or not is usually in our own power; but the Sublime, acting with an imperious and irresistible force, sways every reader whether he will or no.” In On the Sublime I especially enjoy how Longinus speaks of the artistic turn of phrase, the creator's craft, as he cites concrete examples from Homer, the Bible, Sappho, Herodotus, Aristarchus, and so on. The sublime is a simple term that implies so much. The "loftiness and excellence of language" remain the ideal in writing as opposed to fluff or bombast. And yes, Longinus, fully discredits those as false writing. I think today we would call that emotional or reactionary writing. Bombast is simply writing that goes too far. The writer recognizes the need to be original in his use of description and goes overboard. Longinus eventually calls it pathetic. It seems everyone wants to be original. Too true. In Part XV, Longinus provides real examples from Homer, Sophocles, and others that we can imitate. Grand language and perfectly crafted imagery are praised most, but his third and fourth principles are the most practical. Combine figures of speech or rhetorical devices for the most effect. A “close and continuous series of metaphors” is distinctive. Use conjunctions intentionally. Arrange your words in a certain and best order. There is so much more to his advice and criticism, but I especially appreciate Longinus’ analysis of a writer’s style. After we have picked at all the parts, how do we determine what the best writing is? His final pages explore this very question-- Is it not worthwhile to raise the whole question whether in poetry and prose we should prefer sublimity accompanied by some faults, or a style which never rising above moderate excellence never stumbles and never requires correction? ... these are questions proper to an inquiry on the Sublime, and urgently ask for settlement." And Longinus finds it hard to do. At first, he says a reader can discern an innate harmony within an essay. The reader simply knows it is sublime writing. But then, Longinus provides several examples of what sublime language is not. In other words, good writing remains to this day something easy to recognize yet hard to define.

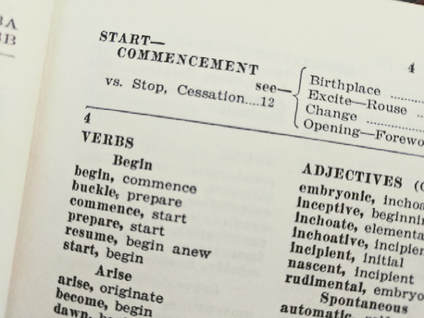

Read "On the Sublime" at Project Gutenberg. Dictionary and thesaurus apps. Etymology and word roots. Language study and Interlinear Bibles. Writing tools in this century are at our fingertips. Yet as I work on my first novel, the most unusual resource has resurfaced—a 1929 Hartrampf’s Vocabulary Builder. I call it my fat word builder. I admit it’s been abandoned for a while on our bookshelves, possibly for ten years, but now—now it’s a rarefied gem in my eyes. Yes, it’s a single book. It has only been recently digitized, and there are many newer editions. Its genius resides in the collection of associated meanings, not just straight synonyms. Let me give you an example from my summer editing work. In my novel's first draft, I have definitely overused certain words like come, wind, were, and a most heinous repetitive phrase--began to. Apparently my heroine Carina likes to begin things. She began to sit or stand. She began to crouch. She began to laugh. Goodness. I promise she finishes things. Really. Now for the edits with Hartrampf's help. I look up the word "begin" in the back index. I'm delighted to find an entire page devoted to its use. The top of this page says to see other possible connections for "start" or "commencement." A handy list with additional pages is right there: birthplace, excite—rouse, change, opening—foreword, musical beginnings, time preceding, or cause. Which kind of "begin" do I want? I could flip to any of those or look below at the parts of speech: And this is just one-eighth of the page. The word wonder continues with many family and neighbor words for "begin." For my character, though, I found that many times she was not truly beginning something. Instead of "With knife in hand, Carina began to crouch..." I realized she wasn't beginning anything. "With knife in hand, Carina crouched..." was more accurate and less wordy. Of course, I could have said, "She prepared herself." In reality "crouched" became the best fat word. Yes, fat. These words contain action and image and power.

As a writer, I can say in all sincerity that I have finally found a happy and pleasant use for the word fat. AGES AGO I took a college course titled “History of the English Language.” In the textbook, Pyle and Algeo argue that language development makes us human. They begin with what we know—speech comes first then writing. Simply put, we can talk before we can write. There are spoken languages in fact with no written form. In spoken language, inflection and stress provide intended meaning. Writing itself distinguishes meaning through its process, but it is useless without words. Words are building blocks, units, ingredients, pieces of a sentence or thought puzzle. But before it entered an English dictionary, the word word was known by the Greeks as logos. In pre-Socratic philosophy it was the principle governing the cosmos because it encapsulated human reasoning. The Sophists later saw it as the topic of rational argument or the arguments themselves. The Stoics viewed logos as nous—the active, material, rational principle of the cosmos that was identified with God. It was both the source of all activity and generation and the power of reason residing in the human soul. In Judaism, logos becomes the living, active word of God. It is creative power, and it is God’s medium of communication with mankind. In Christianity, logos becomes the creative word of God which is itself God incarnate in Jesus in John 1.

Words. As I write this summer, I am ever conscious of how words are used, and not just mine. The writer of Ecclesiastes 3 might describe it this way—words are used to inspire fear, to bring wisdom, to bring joy, to show emotion, to display passions, to attack or defend, to bring comfort, to encourage, to belittle or tear down, to cause pain, to bring healing, to mend. Whether I write fiction or nonfiction, blogs or essays, speeches or stories, the inherent caution is there. My words, our words, have life as we give them. As writers, readers, and speakers, we share a responsibility to use them well. IN THE PAST MONTH, I'VE TWEAKED A LOT. I’ve tweaked curriculum, articles, even the brightness of my book cover and its font size. I've tweaked my website, but I’ve also tweaked my closet apparently. Maybe I even tweaked my foot when I stepped on a backyard mole hill. When it was first recorded in Old English in the 1600s, tweaking used to mean pinching, as in tweaking or tugging someone’s nose. Then it meant plucking, like picking lint off of a shirt. I don’t think I’ve managed to pinch or pluck anything I’ve written, but I may have plucked a few things from my closet that I don’t wear. Now that I consider it, I do pluck things from what I write. I have to so I can add other words. Tweaking means to make a fine adjustment. Tweaking really is refining, and refining is all about process, not perfection. It requires time and reflection and a good deal of plain old thought. I don’t want to be the fool described in Ecclesiastes 10:14 who just multiplies his words. That just implies empty quantity. A good word encourages the heart and strengthens it (Proverbs 12:25). Those words are agreeable and bring pleasure and make you stand taller. Perhaps one of the most valuable parts of the tweaking process is that God can reveal His wisdom to us if we wait and rest without trying to fill a page just to fill it. In Proverbs 8, Wisdom herself says, I have counsel and sound wisdom; I have insight; I have strength. And that is my hope and prayer for the words that I write. Let tweaking be a refining. All the words of my mouth are righteous; TEACHING MY STUDENTS how to improve their own writing is no easy task. I emphasize content and typically focus on one to two stylistic elements per assignment. At the beginning of the school year, I quickly noticed that my seniors were overfond of the verb “use” in most any casual or formal writing assignment. We quickly built a synonym base for the word on the whiteboard and discussed connotations. For several months, I had them search and highlight the word, allowing for a single use. As I worked on my novel these past months, my editor had to repeatedly teach me how to balance my use of active and passive voice in both dialogue and narration. Repeatedly. It took a number of attempts for my brain to get it. And practice was very much a part of the process. My point is that it often takes mini-lessons like these as we each take steps in our writing or even speaking. And that is when writing style guides can be such a help. But forget writing classics like Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. The concept of spelling out rules with writing examples was tackled well before the 20th century. Think of Aristotle’s Poetics in 4th century BC. Though he focuses on drama and epic, he does address the use of language and a playwright’s diction. But I would be remiss if I didn’t also consider a short but splendid stylebook of the first century, one that considers the written and the spoken word. More than our contemporary guides, Cassius Longinus explores the motive of the writer. Why is he writing? What is his end? But more importantly, can we attain sublimity of language? Are we capable of learning it? A lofty passage does not convince the reason of the reader, but takes him out of himself. That which is admirable ever confounds our judgment, and eclipses that which is merely reasonable or agreeable. To believe or not is usually in our own power; but the Sublime, acting with an imperious and irresistible force, sways every reader whether he will or no.” In On the Sublime I especially enjoy how Longinus speaks of the artistic turn of phrase, the creator's craft, as he cites concrete examples from Homer, the Bible, Sappho, Herodotus, Aristarchus, and so on. The sublime is a simple term that implies so much. The "loftiness and excellence of language" remain the ideal in writing as opposed to fluff or bombast. And yes, Longinus, fully discredits those as false writing. I think today we would call that emotional or reactionary writing. Bombast is simply writing that goes too far. The writer recognizes the need to be original in his use of description and goes overboard. Longinus eventually calls it pathetic. It seems everyone wants to be original. Too true. In Part XV, Longinus provides real examples from Homer, Sophocles, and others that we can imitate. Grand language and perfectly crafted imagery are praised most, but his third and fourth principles are the most practical. Combine figures of speech or rhetorical devices for the most effect. A “close and continuous series of metaphors” is distinctive. Use conjunctions intentionally. Arrange your words in a certain and best order. There is so much more to his advice and criticism, but I especially appreciate Longinus’ analysis of a writer’s style. After we have picked at all the parts, how do we determine what the best writing is? His final pages explore this very question-- Is it not worthwhile to raise the whole question whether in poetry and prose we should prefer sublimity accompanied by some faults, or a style which never rising above moderate excellence never stumbles and never requires correction? ... these are questions proper to an inquiry on the Sublime, and urgently ask for settlement." And Longinus finds it hard to do. At first, he says a reader can discern an innate harmony within an essay. The reader simply knows it is sublime writing. But then, Longinus provides several examples of what sublime language is not. In other words, good writing remains to this day something easy to recognize yet hard to define.

Read On the Sublime at Project Gutenberg. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed