|

It was a simple tweet. I posted a picture from the second day of school, showing my own annotations of a C.S. Lewis essay with the caption, “Teaching students annotation means modeling my own.” To my surprise, author Stephen Chiger responded that he taught the same, most notably in his book Love & Literacy published in 2021 for Uncommon Schools, a public charter network in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Intrigued, I wanted to see if a design to foster reading and literacy in urban public schools might share some practices with classical education. The premise of the book is a true ideal: “This is what love in a literacy classroom looks like: a love for the conversation, love for the text, and love for the ideas they both spark. When that includes all students, magic happens.” I kept reading. Once again, I turn to preparing for the summer conference season. I've presented several workshops on poetry over the years, but for this summer, I dug a bit deeper. I asked myself, "How have I taught poetry?" In my first years of teaching high school juniors in a public high school, our American Literature textbook included the usual poets and poems—Anne Bradstreet, Phillis Wheatley, William Cullen Bryant, and so on. My classes and I dutifully read those poems aloud and lightly discussed them. I dutifully assigned the printed discussion questions in the textbook as homework. And the next day, my students turned in their dutiful attempts at answers. Duty pervaded all. We had done our part and moved on through the textbook. Duty pervaded all." When our boys were older and I returned to teaching, in a classical school this time, I heard about how teaching with passion was contagious. Well of course! I had to try it out with poetry. Trust me, my 8th and 9th grade classes were likely overwhelmed by my enthusiasm and my rousing rendition of Whitman's "O Captain, My Captain". Somehow I thought that keeping my students' attention equaled mutual enthusiasm. It did not. I next began dissecting the poems into pieces, demanding that every tiny part be labeled. Unbeknownst to me, my actions sucked out the very life of the poem at hand. I continued this process for several years and could not understand why my enthusiasm and supposed expertise did not transfer to my classes as a whole. It was not my students. I came to see that only when I happened to read C.S. Lewis's Experiment in Criticism for the first time. He writes, The literary sometimes ‘use’ poetry instead of ‘receiving’ it. They differ from the unliterary because they know very well what they are doing and are prepared to defend it. ‘Why’, they ask, ‘should I turn from a real and present experience—what the poem means to me, what happens to me when I read it—to inquiries about the poet’s intention or reconstructions, always uncertain, of what it may have meant to his contemporaries?’ There seem to be two answers. One is that the poem in my head which I make from my mistranslations of Chaucer or misunderstandings of Donne may possibly not be so good as the work Chaucer or Donne actually made. Secondly, why not have both? After enjoying what I made of it, why not go back to the text, this time looking up the hard words, puzzling out the allusions, and discovering that some metrical delights in my first experience were due to my fortunate mispronunciations, and see whether I can enjoy the poet’s poem, not necessarily instead of, but in addition to, my own one?” (151-152). I had been a thief! I had not given my students the space to delight in the poem itself. I had forced my students to use poetry.

In his Preface to Paradise Lost, Lewis says that "the old critics were quite right when they said that poetry 'instructed by delighting.'" In all my learning, in all my best intentions, I had somehow missed this step. My approach to teaching poetry in a classroom setting is quite different now, and I'm still learning. My students and I read a poem aloud and silently several times. I engage the class with questions that most resemble Charlotte Mason's narration approach. I make notes of the questions they ask me and each other. I rarely demand that my students identify parts and pieces unless the poem shouts at us to do so. I offer historical or authorial context only as their questions demand. This simplicity has created a freedom from legalistic analysis. It has given me and my students the opportunity to receive the beauty of words. Caldwell, ID. In 1513, after serving for years in the courts of Florence, Niccolò Machiavelli found himself on the losing side of a Medici plot and was exiled from his beloved city. He was likely tortured before he left. In his new life, he farmed on his family estate and spent his days debating peasants in the local inn. But that was not all. He described the rest of his day in a remarkable and justly famous letter to his friend Francesco Vettori:

When evening comes, I return to my home, and I go into my study; and on the threshold, I take off my everyday clothes, which are covered with mud and mire, and I put on regal and curial robes; and dressed in a more appropriate manner I enter into the ancient courts of ancient men and am welcomed by them kindly, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born; and there I am not ashamed to speak to them, to ask them the reasons for their actions; and they, in their humanity, answer me; and for four hours I feel no boredom, I dismiss every affliction, I no longer feel poverty nor do I tremble at the thought of death: I become completely part of them. Roosevelt Montás, the author of Rescuing Socrates, was likewise welcomed kindly into these ancient courts after finding a whole set of Harvard Classics in the garbage and—due to limited space for books in the Queens apartment of his teen years—saving the Plato volume from suffering the fate of the rest of the series. Like Machiavelli, he is also unashamed to speak with the ancient men and to question them. His new book is a generous and magnanimous account of his own initiation into the world of classics via the Columbia College Core Curriculum, as well as a thoughtful record of his continued engagement with them in many classrooms at Columbia and elsewhere.... In the history of education in America, many Americans no longer know how common schools became more than an idea. Nor do they know who made the first strides in these efforts.

Thomas Jefferson attempted to establish a decentralized public school system more than once, a plan based on localized districts within counties. In his 1778 “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge,” he stressed the need for vigilant citizens who would constantly be on guard against the ambition of rulers, especially at the state or federal levels. Jefferson wanted to educate all students as future citizens in a republic and at the same time provide expanded opportunities for men to develop into the future political leaders of Virginia. At his 1838 Lyceum Address in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln advocated that schools should teach a reverence for our American democracy: “Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother, to the lisping babe, that prattles on her lap—let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in Primers, spelling books, and in Almanacs;—let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation.” Building on this idea of citizenship, William Holmes McGuffey (1800–1873) strove to openly cultivate Christian character by developing readers in the growing American West independent of British influence. The McGuffey Readers introduced students to the classics, to morality, and to good character. Seven million readers were sold before 1850 with thirty-seven states adopting them by 1890. McGuffey’s influence held for decades. In his examination of McGuffey’s life and curriculum, John H. Westerhoff weaves a biography within a fascinating history of education in the early 1800s. The idea of common schools was growing. Westerhoff’s research clearly shows how McGuffey and his original Readers made a significant impact on nineteenth-century education through the use of moral teaching, civics, story, and phonics.... Long ago I took an undergrad course titled Oral Interpretation of Literature. I needed two speech classes to graduate with my education degree, and it happened to fit my schedule. I had no idea what I was walking into. I didn't know that a drama professor taught it. Like myself, most of the students were education majors thinking we had found an easy class to balance out our heavier ones. No textbook required. Our first assignment was to take turns standing in front of the class to read “Dover Beach.” We were to read aloud and keep eye contact. What we didn't know was that we would be excoriated for everything from enunciation to volume to facial expression and posture. It was eye-opening to say the least. I had no expectations. But Professor Lewandowski did. Within two weeks I had two Cs and I was proud of them. Professor Lew promptly coached us as he would an actor presenting a monologue, yet he told us the class was not about drama. Everything we said was about expression, the value of words. He thought that teachers could perform not for performance’s sake, mind you, but because that was how you appreciated the words you said. He reminded us that we would have a captive audience every day of the week in our classrooms after all.

Every other week we presented a poem, a passage from a novel, or a bit from a short story or a play. We learned from each other's mistakes, but we also learned from each other's presentations. And by presentation I mean that moment of beauty when the words, the volume, and the expression create a moment of beauty for the audience, a moment of awe. After presenting four times in class, I still had a C. I was dumbfounded because I was trying my hardest. So I finally stayed after class and asked for help. I wanted to figure out this riddle, this thing I didn't understand how to do. He spent ten minutes helping me polish one section of Rossetti’s “Goblin Market,” just one. But it was enough. After all these weeks, this little bit of practice and coaching was what I needed. By repetition, he taught me in those moments to read the lilt in the Rossetti’s rhyme, to play with different words. I don't remember if I got an A or a B by the end of the semester, but I do remember improving, performing a section of Leo Tolstoy's “The Death of Ivan Ilyich.” It was a challenge, but I tried and performed, reading and engaging the audience, and using the tools Professor Lew had shown me. I may have done a decent job. After all these years, decades, I still have a file of notes from that course. I have not forgotten. But more than that, I know interpreting the literature and poetry I teach adds everything to how my students hear. I only hope that my efforts lead my students to the same wonder I experienced at age 19. I enjoyed a unique phone call recently. One of my former students reached out for help with a long essay. As a hopeful history major, Eric wanted to submit a college application essay on a historical subject he loved—the French Revolution. He had narrowed the topic to the role of Royalist journalists and had completed all of the research, including some amazing digitized letters and propaganda from that time period. Unfortunately, the essay had practically become a list of quotes and sources and key figures. Some connections among them had been made, but it wasn’t coherent. Yet. We circled back to his premise, and I asked, “What is your point? What are you leading us to understand?” That helped a little bit, but Eric said he needed more time to think about it. So of course I asked him to revise it further, and he immediately asked, “What does that word mean?” Good question. From Latin and French roots, revise means to look at or look over again. It sounds horribly simple: By the 1590s, revise came to mean "to look over again with intent to improve or amend."* But that doesn’t help the student know what to do. They understand by context that they must make corrections. These are the concrete elements, the checklist, the things the teacher may have noted like “add a transition phrase here” or “choose a stronger verb” or “check for commas.” This is editing, not rewriting or revising. But Eric had moved beyond concrete editing already. As teachers, we have to remember that we are both readers and writers. If we instruct in writing, it’s because we read first. In God in the Dock, C.S. Lewis reminds us that “The reader, we must remember, does not start by knowing what we mean. If our words are ambiguous, our meaning will escape him. I sometimes think that writing is like driving sheep down a road. If there is any gate open to the left or the right, the reader will most certainly go into it.” And that compelled me to ask Eric a few questions: How can you make your writing more clear? Is there a sentence or thought that obscures or leads you away from what you really mean to say? If you were an editor of a historical journal, what would you cut as excess?” In this instance, it was a fruitful exercise. He immediately cut several “interesting” facts that did not lead to his real point—the Royalists believed revolution was sin because they were preserving the semblance of Jesus Christ, King Louis XVI. Eric eliminated four sentences in four pages. He told me it was easier to see once I mentioned that sentences can lead away as well as lead us to the premise. It may not seem like a lot, but by removing them, he could more easily see what needed to be connected.

I hesitate to use the phrase “big picture,” yet I would ask if we can see the essay as a whole. Can we see our way in the forest through the leaves of words or has the path been obscured? Before, fascinating tidbits led Eric into the weeds and fields beside the path. By eliminating what led him away, he gained the path again. Each fact, each quote, each sentence connected his journey along the path of the essay. And seeing might be the point of revision, to re-vision our thoughts. *Online Etymology Dictionary I received a rejection last week. From one year ago. An agent whose work I admire had requested a full manuscript for my middle grade novel. I enjoyed the read – you’ve got a great voice here, and I really liked the concept, but in the end, I just didn’t fall enough in love to be able to offer representation.” For those in the writing trenches, you’ll recognize the wording of a standardized rejection. It’s neither encouraging nor discouraging. From an agent, it could mean “Your story is not for me” or they (or their assistant) really weren’t captured enough to read it, let alone provide feedback.

Rejection is an odd thing for me as a literature teacher because I delight in words. Reading, absorbing, experiencing, teaching, analyzing, writing. As a teacher, I hope to never suck the joy out of the reading experience for my students. I certainly endured more than one class in high school and college that did that well. Analyze. Pull the story apart. Pick it to death. Put it back together. Mash it into the meaning the teacher wants. Textbooks can often be structured that way too. I wonder if many are built for overworked teachers, to make their lives easier. They might include commentary on a theme, different levels of discussion questions, and ideas for essays. Sometimes I’d rather they didn’t. It can be too prescriptive because the textbook authors are giving you their meaning. On the surface, it’s like saying that teachers and students alike are incapable of thinking through these things. It’s practically miraculous that any student comes out of that system having enjoyed the story still. And that’s the odd parallel. In writing fiction, I have to be aware of all of the parts, like ingredients in a recipe. I know what I’m making, but every separate thing must come together. I have to be intentional. I have to be aware of word choice, lexile, backstory, setting, point of view, tone, characters’ needs and wants, the arc of each character, the arc of the plot, scene structure—so many things. It’s the opposite of how I read and how I teach reading and writing. I realize now that I most appreciate a holistic approach. I do think all of the parts come together as a whole, a synchronicity of sorts. For some writers it comes naturally. For others, like me, it comes through labor and training, especially through the imitation of others. And that gives me every hope that as I teach my students parts of the whole, I can do it in a way that doesn’t suck the joy out of the reading experience. We don’t have to notice absolutely every thing in a story to enjoy it. As I lead a class, I can model that. I can choose to emphasize perhaps two or three things an author has constructed. As I am aware, even hyper aware of what an author has done in the story structure, I am able to encourage my students to appreciate the grand design. Every now and then I land upon a book that causes me to pause, to slow my reading. My desire to absorb what I read surpasses my desire to finish the book, even such a short one as A Confession. Leo Tolstoy was 51. Having gained fame and fortune after publishing War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877), he earnestly questioned his purpose in life. Tracing his childhood and young adult life at first, Tolstoy admits that he never thought about what he believed or why. He saw no reason to continue in the Orthodox Christianity he was brought up in. People at a certain level of education didn’t need faith, he thought. “Then as now, it was and is quite impossible to judge by a man's life and conduct whether he is a believer or not.” Tolstoy did not see how religious doctrine played a part in anyone’s life—“in intercourse with others it is never encountered, and in a man's own life he never has to reckon with it.” Instead of pursuing what he saw as an empty faith, he says, “I tried to perfect myself mentally—I studied everything I could, anything life threw in my way; I tried to perfect my will, I drew up rules I tried to follow.” His self-centered attempts soon led to wanting to appear more perfect than others. So he did whatever he wanted, and the older he grew, and the more he watched others, he knew he had to make progress. He wanted to be good but saw that he was alone in this desire. As he describes his military life, Tolstoy lists all of his sins, but as he turned to writing in his twenties, his fellow writers were no different at heart than the soldiers and officers he lived among for so long. It wasn’t long before he realized that “the superstitious belief in progress is insufficient as a guide to life. I had to know why I was doing it.” It makes me remember a phrase from long ago, “the cult of progress.” In a writer’s life today, it’s still a mantra. But then in Chapter 3, Tolstoy turns his thoughts to education as he considered plans for his own children someday. “I would say to myself: ‘What for?’” He was really asking how do we teach if we’ve never been taught-- In reality I was ever revolving round one and the same insoluble problem, which was: How to teach without knowing what to teach. In the higher spheres of literary activity I had realized that one could not teach without knowing what, for I saw that people all taught differently, and by quarreling among themselves only succeeded in hiding their ignorance from one another. But here, with peasant children, I thought to evade this difficulty by letting them learn what they liked. It amuses me now when I remember how I shuffled in trying to satisfy my desire to teach, while in the depth of my soul I knew very well that I could not teach anything needful for I did not know what was needful. After spending a year at school work I went abroad a second time to discover how to teach others while myself knowing nothing." Tolstoy clearly recognizes the voids within him. He tried to replace an absence of faith in God with a faith in himself. He tried to give himself purpose, trying to attain status and fame in the military and as a writer before turning to teaching peasant families, all before he married and had a family. His striving had left him empty, and with his retrospective, Tolstoy saw himself for what he lacked.

I’ve only read these first chapters of A Confession, and I think I’ll reread them before moving on. Maybe it’s because I’m near the same age as he was when he examined his life. Maybe it’s because, when I'm alone, I question the fruitfulness of my life. Regardless, Tolstoy gives us much to ponder. What do we truly value? Do I know what I believe? Do I know my purpose? “The truth is that nothing is less sensational than pestilence, and by reason of their very duration, great misfortunes are monotonous.” As an independent teacher, I was eager to make a curriculum shift to my World Literature class this school year. I added Albert Camus’s best-selling novel The Plague because I wondered how my students would see a fictional epidemic.

Why not use our times as a secondary context to the novel? I was not disappointed by our discussions in September. Though Oran, Algeria, is beset by plague, the novel is relatively static. It is also uniquely ahistorical. It may be set in 1947 but there are no references to World War II. Neither the Arab nor African populations of Oran are mentioned. Centuries of segregation are never described. And then there are the facts. It is not possible for a town to have sustained itself for the period of time described in the novel. Yes, the characters are realistic, but the novel is not. This unique paradigm, however, lends itself to the timelessness Camus captures. Within the bubble of Oran, Camus’s commentary as narrator allows him to describe the “portents and panic” with searing truth. As COVID broke out in March and April, The Plague, of course, was referenced and quoted repeatedly. Penguin Classics has already had to reprint it twice this year. From my class discussions, here are my top timeless quotes:

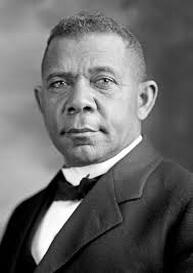

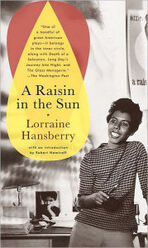

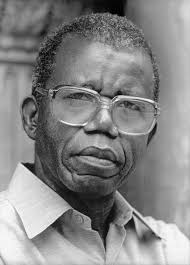

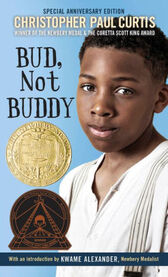

Spanning generations and political views, the authors I teach here have influenced how I see people, how I see my own students, and hopefully how we all see the world we live in.  1. Booker T. Washington If you read my blog, you know I’m an ardent fan of Washington and his words. [See An Educator’s Devotion and Booker T. Washington’s Compromise.] When I read his Character Training (1902) in January this year, I was inspired to be more intentional in laying excellence as a standard in my classrooms. I’ve continued to read more of his works and biographies by others, including the singular The Negro in the South lectures with W. E. B. Du Bois. It's interesting to see the two men juxtaposed. Even if you've never read these men before, Washington is naturally more positive in these lectures while Du Bois's deep sense of injustice permeates his words.  2. Lorraine Hansberry Just as Washington believed hard work and perseverance were noble efforts, Hansberry depicted a different reality in the 1950s, the limitation of the American Dream for black Americans. I know it’s not her only work, but her play A Raisin in the Sun (1957) is such a living picture. She writes to her mother, “It is a play that tells the truth about people. But above all, that we have among our miserable and downtrodden ranks people who are the very essence of human dignity.” It is the essence of a merciful humanism, a good kind, that stirs understanding in the middle of activism.  3. Chinua Achebe Like Hansberry, Achebe was published by the age of 28. I first read Achebe in college under the tutelage of a visiting professor from Nigeria. More than the class discussions about Things Fall Apart (1958), I remember the sense of my cultural ignorance. Yes, suffering, pride, and injustice are human frailties, but more than that, a native son can criticize his own country for allowing Western values to compete with traditional African culture. I also read his second novel No Longer at Ease (1960) and include my reflections here in Reading Binges. It very much reminded me of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.  4. Christopher Paul Curtis I first read Bud, Not Buddy (2000) with my oldest son when he was in third grade. Bud, a ten-year-old African American boy, runs away from his abusive foster family in Flint, Michigan. He embarks on a journey to find his father, enduring the fears and horrors of the Great Depression. Written in a strong, compelling voice, Bud, Not Buddy beautifully evokes what life was like for African Americans, especially musicians, in Michigan during the Depression. Since then, my family was captured by Curtis’s historical fiction, having read The Watsons Go To Birmingham and Elijah of Buxton. I continue to recommend Curtis to families looking for compelling historical reads.  5. Harriet Ann Jacobs At the recommendation of Karen Swallow Prior, I finally read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) two years ago. Not only had I never heard of the account, but my students hadn’t either. I now include excerpts from Jacobs after I teach Washington's Up from Slavery. Jacobs addresses her autobiography to white Northern women who fail to comprehend the evils of slavery. Published in 1861, it is a harrowing account of hiding for seven years before being reunited with her children in New York. After the Civil War, Jacobs traveled to Union-occupied parts of the South together with her daughter to organize help and begin two schools for fugitive and freed slaves. Her book was well-received in America and England. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed