|

No other author has so immediately affected my perspective on work as Josef Pieper. In my mind, work was separate from the rest of life. Working hours have always been a discrete part of my day since I took my first job as a teenager. Maybe this division is inherent to American culture and how I grew up, but in Pieper’s mind, work is part of our response to the gift of life.

Though published decades ago, German philosopher Josef Pieper’s commentaries on work, leisure, and festivity bring to light two deficits within our culture today—true community relationship and conscious introspection. His works, Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1948) and In Tune with the World: A Theory of Festivity (1965), posit not a solution to our culture’s dis-perspective, but a call to return to a meaningful and fruitful life. If we can’t recognize leisure, then our culture is endangered. But leisure is a tricky word in the twenty-first century. Is it welcoming visitors at our leisure? Is it reclining on a couch in a leisure suit? Is it being free from work demands? Is it the opposite of work? What kind of leisure is this? . . . It was a simple tweet. I posted a picture from the second day of school, showing my own annotations of a C.S. Lewis essay with the caption, “Teaching students annotation means modeling my own.” To my surprise, author Stephen Chiger responded that he taught the same, most notably in his book Love & Literacy published in 2021 for Uncommon Schools, a public charter network in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Intrigued, I wanted to see if a design to foster reading and literacy in urban public schools might share some practices with classical education. The premise of the book is a true ideal: “This is what love in a literacy classroom looks like: a love for the conversation, love for the text, and love for the ideas they both spark. When that includes all students, magic happens.” I kept reading. Caldwell, ID. In 1513, after serving for years in the courts of Florence, Niccolò Machiavelli found himself on the losing side of a Medici plot and was exiled from his beloved city. He was likely tortured before he left. In his new life, he farmed on his family estate and spent his days debating peasants in the local inn. But that was not all. He described the rest of his day in a remarkable and justly famous letter to his friend Francesco Vettori:

When evening comes, I return to my home, and I go into my study; and on the threshold, I take off my everyday clothes, which are covered with mud and mire, and I put on regal and curial robes; and dressed in a more appropriate manner I enter into the ancient courts of ancient men and am welcomed by them kindly, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born; and there I am not ashamed to speak to them, to ask them the reasons for their actions; and they, in their humanity, answer me; and for four hours I feel no boredom, I dismiss every affliction, I no longer feel poverty nor do I tremble at the thought of death: I become completely part of them. Roosevelt Montás, the author of Rescuing Socrates, was likewise welcomed kindly into these ancient courts after finding a whole set of Harvard Classics in the garbage and—due to limited space for books in the Queens apartment of his teen years—saving the Plato volume from suffering the fate of the rest of the series. Like Machiavelli, he is also unashamed to speak with the ancient men and to question them. His new book is a generous and magnanimous account of his own initiation into the world of classics via the Columbia College Core Curriculum, as well as a thoughtful record of his continued engagement with them in many classrooms at Columbia and elsewhere.... In the history of education in America, many Americans no longer know how common schools became more than an idea. Nor do they know who made the first strides in these efforts.

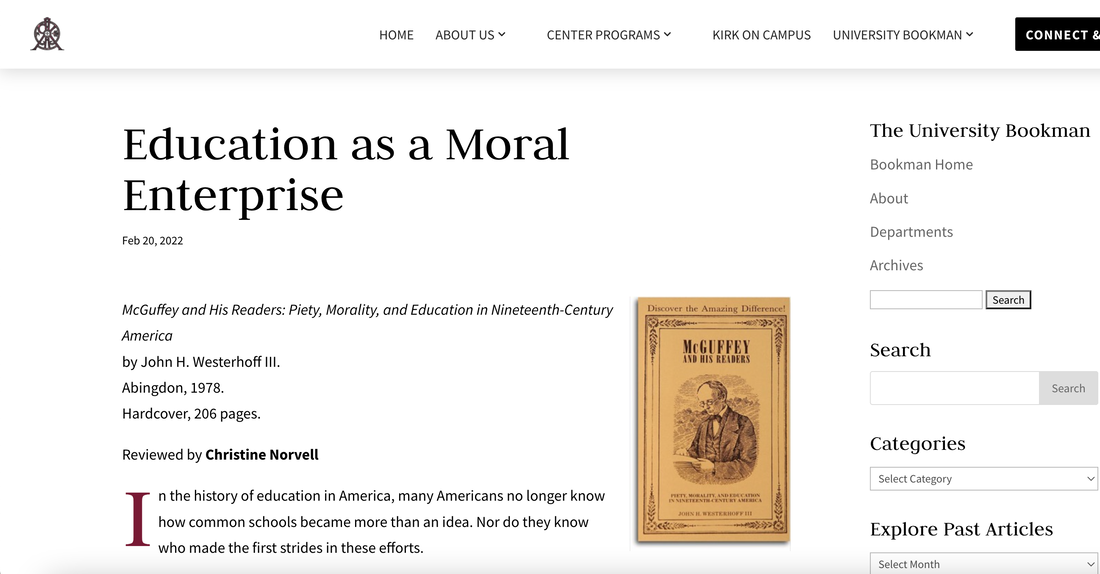

Thomas Jefferson attempted to establish a decentralized public school system more than once, a plan based on localized districts within counties. In his 1778 “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge,” he stressed the need for vigilant citizens who would constantly be on guard against the ambition of rulers, especially at the state or federal levels. Jefferson wanted to educate all students as future citizens in a republic and at the same time provide expanded opportunities for men to develop into the future political leaders of Virginia. At his 1838 Lyceum Address in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln advocated that schools should teach a reverence for our American democracy: “Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother, to the lisping babe, that prattles on her lap—let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in Primers, spelling books, and in Almanacs;—let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation.” Building on this idea of citizenship, William Holmes McGuffey (1800–1873) strove to openly cultivate Christian character by developing readers in the growing American West independent of British influence. The McGuffey Readers introduced students to the classics, to morality, and to good character. Seven million readers were sold before 1850 with thirty-seven states adopting them by 1890. McGuffey’s influence held for decades. In his examination of McGuffey’s life and curriculum, John H. Westerhoff weaves a biography within a fascinating history of education in the early 1800s. The idea of common schools was growing. Westerhoff’s research clearly shows how McGuffey and his original Readers made a significant impact on nineteenth-century education through the use of moral teaching, civics, story, and phonics.... Sometimes I reread children’s literature because I enjoy being captured again by the quality of writing and the stir of imagination. I read Laura Ingalls Wilder alongside every Louis L’Amour western in my junior high library. Not one librarian said I couldn’t read them because I was a girl, and thankfully, those same librarians pointed me next to Zane Grey. At age 13 and 14, these westerns were deep to me, even if I did recognize the plot patterns. I loved them. Action, mystery, rescue, the setting sun, the lonely West, and often, a misunderstood man.

In the same vein, Jack Schaefer’s very first novel creates a story that’s even more impactful. Shane (1949) began as a short story that was serialized in three parts in Argosy magazine in the late 40s. First titled “Rider from Nowhere,” it wasn’t intended for young children, though it’s certainly suitable. Through the eyes of a child narrator and from his opening description, Schaefer crafts a deeper cowboy character than most, perhaps because we witness Shane’s moral choices and his influence upon an entire family... The world is not always a kind place, said Brother Edik.

We may lose those we love along the way, but unexpected friends, like a goat, can bring delight and comfort. Yes, a goat. In Kate DiCamillo’s The Beatryce Prophecy, the monks of the Order of the Chronicles of Sorrowings are harassed by an ornery goat, one that soon finds a different purpose in comforting a lost girl. Beatryce is found by Brother Edik, who long ago foretold that a girl child “will unseat a king.” But Beatryce doesn’t remember why she fled her home. She doesn’t know she might be important. “Will you write of this in the Chronicles?” she asked. “Will you say that a girl named Beatryce, who does not know where she came from or who her people are, held on to a goat and sorrowed?” “Yes,” said Brother Edik from above her. “It will be written so.” “As something that happened?” said Beatryce. “Or as something that has yet to happen? Will I become a prophecy?” “Oh, Beatryce,” said Brother Edik. I’ve made huge lists of everything I’ve done in my short life. I’ve accomplished so much, and I can show you my work, says Solomon.

It’s too familiar. Lists have been a lifeline for me as a working mom, a salvation of things that would have been forgotten. I’ve accomplished so much, I think. I remembered to buy peas and Band-Aids at the store. I signed and sent the weekly reading logs to school with my sons. I vacuumed one bathroom. So, I pat myself on the back, taking pride in the accomplishment of one day. But does checking things off mean something? It might be encouraging at that moment, for that day, but weeks and months from now, will it mean anything? After all, Solomon darkly reminds us that man takes nothing with him at death (Ecclesiastes 5:15)....  I love a good mess. Over the past week, two handymen have been working on our house, replacing rotted siding and a handful of windows. They have touched almost every room in our house for one reason or another and tend to leave funny little bits behind. As I’m writing this at my bedroom desk, I can see a small plastic package of unopened screws left on my desk. If I walk into my bathroom, I find a new package of long brass wood screws. If I toodle over to my husband’s office, I can see a red-handled wood chisel sitting high up on an upper window sill. Every room has something left behind, or, if I look at it in another way, a tool or supply for equipping us in our repairs. Perhaps it’s more than home repairs because repairs make me think of one book I’ve slowly ingested this summer--Madeline L’Engle’s Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art (1980). You see, in the writing game, I fight discouragement regularly. I fight doubt, purpose, all those things. L’Engle does not deny the negatives and speaks candidly about her “decade of failure” where doubt and guilt consumed her with “bitter lessons” in her writing journey. Her compilation of thoughts on the process of writing amid reflections on her spiritual life has become a nourishing devotional to me in the summer season. We think because we have words, not the other way around. The more words we have, the better able we are to think conceptually." L’Engle consciously turns her focus to how God works through us. “But we also need to be reminded in this do-it-yourself age that it is indeed God who made us, and not we ourselves. We are human and humble and of the earth, and we cannot create until we acknowledge our createdness.” She explores many tangents along the way but always returns to “An artist is a nourisher and a creator who knows that during the act of creation there is collaboration. We do not create alone.” I’ve copied many of these quotes in my writing journal this summer, writing them down over and over. It’s like the life of L’Engle’s words have become my cheerleader, bringing me back to center. When I am constantly running there is no time for being. When there is no time for being there is no time for listening.” And I do want to listen as I read and write. I don't want writing to become my busyness.

To repair is to mend and put back in order. But its Latin root parare means to make ready, to prepare. I trust that I am “making ready” again, preparing for the life where my words fit in the homes God has for them. London, 1945.

World War II is coming to an end. The Blitz, air raid sirens, and bomb shelters are things of the past, but the reality of living with loss in a war-torn city remains. Rationing and deprivation continue. Recovering from the trauma of war and wartime is difficult for everyone, but especially if you’re eleven years old. Brita Sandstrom’s middle-grade novel centers on Charlie who lives with his mom, grandpa, and cat Biscuits. A World War I veteran, his one-armed Grandpa Fritz prepares Charlie for the return of his wounded older brother, explaining that the war experience steals something from people. If a soldier survives, he comes back missing a piece of himself. But Charlie is full of hope. He had promised his brother Theo that he would look after the family and he had. His mother gave him permission to leave school for a time to care for Grandpa on his “down” days when she went to work. Charlie takes care of the shopping and manages the ration cards. He prays daily that Theo will come home and that Theo will be fine. And his prayers work. Theo is returning alive from a hospital in France.... At VoegelinView this month...

It was a classic when it was first published in 1949, but it remains a classic because it is one-of-a-kind. Marchette Chute’s Shakespeare of London is absolutely my favorite biography of Shakespeare because of her contextual approach. Rather than focusing on biographical elements alone, Chute essentially crafts the story of Shakespeare’s life from a paper trail, from wherever she could find town records, lease arrangements, tax papers, theatre programs, personal letters, and really anything in print. She creates a holistic picture of the time period in Stratford-upon-Avon and in London while effectively showing the complexity of the London stage. Chute writes about how Shakespeare’s arrival in London was perfectly timed as the theatres themselves were just blossoming: “William Shakespeare brought great gifts to London, but the city was waiting with gifts of its own to offer him. The root of his genius was his own but it was London that supplied him with favoring weather.” More than one chapter deals with the rigorous training a successful actor had to go through. From the physicality of stunts, fencing, and dancing to the ability to sing and capture an audience with voice, the requisite skills of an actor were truly gifts in a competitive field. The repertoire of one actor, let alone an active company, was a teeming stock of stories. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed