|

No other author has so immediately affected my perspective on work as Josef Pieper. In my mind, work was separate from the rest of life. Working hours have always been a discrete part of my day since I took my first job as a teenager. Maybe this division is inherent to American culture and how I grew up, but in Pieper’s mind, work is part of our response to the gift of life.

Though published decades ago, German philosopher Josef Pieper’s commentaries on work, leisure, and festivity bring to light two deficits within our culture today—true community relationship and conscious introspection. His works, Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1948) and In Tune with the World: A Theory of Festivity (1965), posit not a solution to our culture’s dis-perspective, but a call to return to a meaningful and fruitful life. If we can’t recognize leisure, then our culture is endangered. But leisure is a tricky word in the twenty-first century. Is it welcoming visitors at our leisure? Is it reclining on a couch in a leisure suit? Is it being free from work demands? Is it the opposite of work? What kind of leisure is this? . . . It was a simple tweet. I posted a picture from the second day of school, showing my own annotations of a C.S. Lewis essay with the caption, “Teaching students annotation means modeling my own.” To my surprise, author Stephen Chiger responded that he taught the same, most notably in his book Love & Literacy published in 2021 for Uncommon Schools, a public charter network in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Intrigued, I wanted to see if a design to foster reading and literacy in urban public schools might share some practices with classical education. The premise of the book is a true ideal: “This is what love in a literacy classroom looks like: a love for the conversation, love for the text, and love for the ideas they both spark. When that includes all students, magic happens.” I kept reading. Caldwell, ID. In 1513, after serving for years in the courts of Florence, Niccolò Machiavelli found himself on the losing side of a Medici plot and was exiled from his beloved city. He was likely tortured before he left. In his new life, he farmed on his family estate and spent his days debating peasants in the local inn. But that was not all. He described the rest of his day in a remarkable and justly famous letter to his friend Francesco Vettori:

When evening comes, I return to my home, and I go into my study; and on the threshold, I take off my everyday clothes, which are covered with mud and mire, and I put on regal and curial robes; and dressed in a more appropriate manner I enter into the ancient courts of ancient men and am welcomed by them kindly, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born; and there I am not ashamed to speak to them, to ask them the reasons for their actions; and they, in their humanity, answer me; and for four hours I feel no boredom, I dismiss every affliction, I no longer feel poverty nor do I tremble at the thought of death: I become completely part of them. Roosevelt Montás, the author of Rescuing Socrates, was likewise welcomed kindly into these ancient courts after finding a whole set of Harvard Classics in the garbage and—due to limited space for books in the Queens apartment of his teen years—saving the Plato volume from suffering the fate of the rest of the series. Like Machiavelli, he is also unashamed to speak with the ancient men and to question them. His new book is a generous and magnanimous account of his own initiation into the world of classics via the Columbia College Core Curriculum, as well as a thoughtful record of his continued engagement with them in many classrooms at Columbia and elsewhere.... I’ve made huge lists of everything I’ve done in my short life. I’ve accomplished so much, and I can show you my work, says Solomon.

It’s too familiar. Lists have been a lifeline for me as a working mom, a salvation of things that would have been forgotten. I’ve accomplished so much, I think. I remembered to buy peas and Band-Aids at the store. I signed and sent the weekly reading logs to school with my sons. I vacuumed one bathroom. So, I pat myself on the back, taking pride in the accomplishment of one day. But does checking things off mean something? It might be encouraging at that moment, for that day, but weeks and months from now, will it mean anything? After all, Solomon darkly reminds us that man takes nothing with him at death (Ecclesiastes 5:15)....  I love a good mess. Over the past week, two handymen have been working on our house, replacing rotted siding and a handful of windows. They have touched almost every room in our house for one reason or another and tend to leave funny little bits behind. As I’m writing this at my bedroom desk, I can see a small plastic package of unopened screws left on my desk. If I walk into my bathroom, I find a new package of long brass wood screws. If I toodle over to my husband’s office, I can see a red-handled wood chisel sitting high up on an upper window sill. Every room has something left behind, or, if I look at it in another way, a tool or supply for equipping us in our repairs. Perhaps it’s more than home repairs because repairs make me think of one book I’ve slowly ingested this summer--Madeline L’Engle’s Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art (1980). You see, in the writing game, I fight discouragement regularly. I fight doubt, purpose, all those things. L’Engle does not deny the negatives and speaks candidly about her “decade of failure” where doubt and guilt consumed her with “bitter lessons” in her writing journey. Her compilation of thoughts on the process of writing amid reflections on her spiritual life has become a nourishing devotional to me in the summer season. We think because we have words, not the other way around. The more words we have, the better able we are to think conceptually." L’Engle consciously turns her focus to how God works through us. “But we also need to be reminded in this do-it-yourself age that it is indeed God who made us, and not we ourselves. We are human and humble and of the earth, and we cannot create until we acknowledge our createdness.” She explores many tangents along the way but always returns to “An artist is a nourisher and a creator who knows that during the act of creation there is collaboration. We do not create alone.” I’ve copied many of these quotes in my writing journal this summer, writing them down over and over. It’s like the life of L’Engle’s words have become my cheerleader, bringing me back to center. When I am constantly running there is no time for being. When there is no time for being there is no time for listening.” And I do want to listen as I read and write. I don't want writing to become my busyness.

To repair is to mend and put back in order. But its Latin root parare means to make ready, to prepare. I trust that I am “making ready” again, preparing for the life where my words fit in the homes God has for them. Every now and then I land upon a book that causes me to pause, to slow my reading. My desire to absorb what I read surpasses my desire to finish the book, even such a short one as A Confession. Leo Tolstoy was 51. Having gained fame and fortune after publishing War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877), he earnestly questioned his purpose in life. Tracing his childhood and young adult life at first, Tolstoy admits that he never thought about what he believed or why. He saw no reason to continue in the Orthodox Christianity he was brought up in. People at a certain level of education didn’t need faith, he thought. “Then as now, it was and is quite impossible to judge by a man's life and conduct whether he is a believer or not.” Tolstoy did not see how religious doctrine played a part in anyone’s life—“in intercourse with others it is never encountered, and in a man's own life he never has to reckon with it.” Instead of pursuing what he saw as an empty faith, he says, “I tried to perfect myself mentally—I studied everything I could, anything life threw in my way; I tried to perfect my will, I drew up rules I tried to follow.” His self-centered attempts soon led to wanting to appear more perfect than others. So he did whatever he wanted, and the older he grew, and the more he watched others, he knew he had to make progress. He wanted to be good but saw that he was alone in this desire. As he describes his military life, Tolstoy lists all of his sins, but as he turned to writing in his twenties, his fellow writers were no different at heart than the soldiers and officers he lived among for so long. It wasn’t long before he realized that “the superstitious belief in progress is insufficient as a guide to life. I had to know why I was doing it.” It makes me remember a phrase from long ago, “the cult of progress.” In a writer’s life today, it’s still a mantra. But then in Chapter 3, Tolstoy turns his thoughts to education as he considered plans for his own children someday. “I would say to myself: ‘What for?’” He was really asking how do we teach if we’ve never been taught-- In reality I was ever revolving round one and the same insoluble problem, which was: How to teach without knowing what to teach. In the higher spheres of literary activity I had realized that one could not teach without knowing what, for I saw that people all taught differently, and by quarreling among themselves only succeeded in hiding their ignorance from one another. But here, with peasant children, I thought to evade this difficulty by letting them learn what they liked. It amuses me now when I remember how I shuffled in trying to satisfy my desire to teach, while in the depth of my soul I knew very well that I could not teach anything needful for I did not know what was needful. After spending a year at school work I went abroad a second time to discover how to teach others while myself knowing nothing." Tolstoy clearly recognizes the voids within him. He tried to replace an absence of faith in God with a faith in himself. He tried to give himself purpose, trying to attain status and fame in the military and as a writer before turning to teaching peasant families, all before he married and had a family. His striving had left him empty, and with his retrospective, Tolstoy saw himself for what he lacked.

I’ve only read these first chapters of A Confession, and I think I’ll reread them before moving on. Maybe it’s because I’m near the same age as he was when he examined his life. Maybe it’s because, when I'm alone, I question the fruitfulness of my life. Regardless, Tolstoy gives us much to ponder. What do we truly value? Do I know what I believe? Do I know my purpose? War, or perceived war, affects our imagination. More than one reader shared a war account with me and wondered the same thing I did. During the pandemic, many hospitals and entire cities have been described as battlegrounds in a war against a virus. The word trauma appears regularly. Another reader responded that her foster children experienced the same lack C.S. Lewis observed in his London evacuees. Their imaginations had simply stopped. Her family continues to love and nurture and create opportunities for these children, for their imaginations to work. Play is crucial, she wrote. After a year, they are seeing creativity return. Lewis’s theory about limited imagination in wartime proves true. The imagination can shut down to protect itself from grief, from imagining too vividly what happened. It will try to prevent itself from reliving trauma. The mind and spirit protect themselves. I read parts of Dr. Bessel Van der Kolk’s book, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, to understand a psychiatrist’s perspective. Whether through trauma, abuse, or neglect, traumatized people anticipate rejection and deprivation and are certain new options will lead to failure. When they are compulsively and constantly being pulled into the past, they cannot envision a different future. Dr. Karyn Purvis agrees and advocates for trauma-informed care for children who come from hard places. Severe trauma physically affects brain growth on a physical level. Cognitive processing and emotional regulation slow. Higher level brain growth is stunted. Purvis says that brain behavior must return to the place before trauma happened. We help trauma victims by rewriting their brains with new safe experiences. Some psychologists call this imprinting. Some call it bonding. But all of it relates to resurrecting this thing called imagination. In my reading this week, I’ve realized the deprivations of the pandemic have affected me more deeply than I had guessed. Is that too simple? I’m pretty sure I’ve ignored it. For me, it’s a first step—acknowledging that it’s there. Many of you have been shaped by layers of loss that go deeper. Maybe you've thought the word trauma is too strong. Your body, mind, and imagination have all been affected. I can’t offer a plan of action or the care of a therapist, but I can offer encouragement as we seek together to understand this thing called the imagination. Imagination is integral to the quality of our lives. It fires our creativity, relieves our boredom, alleviates our pain, enhances our pleasure, and enriches our most intimate relationships. Without it, hope fades. We are designed this way. In the words of George MacDonald, The imagination of man is made in the image of the imagination of God. Everything of man must have been of God first; and it will help much towards our understanding of the imagination and its functions in man if we first succeed in regarding aright the imagination of God, in which the imagination of man lives and moves and has its being." Please share any resources and thoughts below.

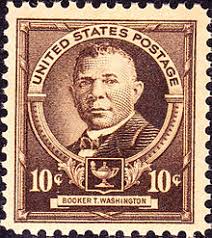

I FIRST READ Up from Slavery ten years ago and was quickly surprised that it wasn’t required reading for every educator. In his autobiography, Booker Taliaferro Washington (1856-1915) leaves us an equal bounty of moral wisdom and caution that all began with his dream to learn. Education is central to his story. He writes, There was never a time in my youth, no matter how dark and discouraging the days might be, when one resolve did not continually remain with me, and that was a determination to secure an education at any cost. Once the slaves were freed after the Civil War, Washington, his mom, and siblings walked from Franklin County, Virginia, to the salt mines of Malden, West Virginia, to join his stepdad who had found work there. In a rough shanty town of whites and blacks, Washington envied the one young colored boy who read the evening papers aloud to his neighbors. Within a few weeks, Washington taught himself to read the alphabet. Within a few months, the colored people had found their first teacher, a Negro boy from Ohio who was a Civil War veteran. The families all agreed to board him as pay, and he taught children and adults alike. Washington relates, it was a whole race trying to go to school. The oldest Negroes were determined to read the Bible before they died, and every class, even Sunday school, was full of eager learners of every age. Unfortunately, Washington was not one of them. Washington leaves us an equal bounty of moral wisdom and caution that all began with his dream to learn.  Washington’s stepdad found him to be more valuable as a worker and would not release him from his shifts. For months, while he worked at the head of the mine, Washington watched the Negro children walk to and from school. Eventually, he was able to secure lessons at night and eagerly devoured all he could. As time passed and he continued to press his stepfather, Washington finally won. He was allowed to work early, go to day school, work two more hours late afternoon before returning home—all at the age of eleven. Washington worked as a salt packer, coal miner, and house servant, always attending school in the off hours. By 1872 at the age of sixteen, he traveled for a month to reach Hampton, Virginia, to attend a teacher school for African Americans. He served as the school janitor to support himself and graduated in three years with a certificate to teach in a trade school. The desire to learn was his work ethic. His work ethic was his desire to learn. As Washington saw his dream to educate others come to fruition, he taught at a local school in Hampton then in a program for Native Americans before agreeing to train Negroes at an agricultural and mechanical school in Alabama, the Tuskegee Institute. He writes humbly and fluently of his years there in leadership, even as his national influence grew. Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Slave or free, shallow or deep, useless or useful. The distractions of life, the shiny things, are superficial. Yes, we agree. Our country, our people, this humanity, cannot grow until we see past them and move toward seeing each other in every skill or occupation or gifting as God designed us.

ARISTOTLE MAY HAVE GOT IT RIGHT. His emphasis on logic allowed him to view slaves and slavery, men and property owners, more rationally and compassionately than any other leader. This single topic of his time shows us a broad yet thorough picture of how true reasoning works and works fairly. The concept and practice of enslaving other peoples has existed for centuries. In most ancient societies, slavery was not only custom but also necessity. Without this foundation of labor, the very structure of early societies could fail. In ancient Greece, Aristotle argued that slavery was a necessity, and it could be either just or unjust in practice; yet he also acknowledged that rational slaves could have souls (which begs another question of course) and deserved to be freemen. This seeming discrepancy points to his growing awareness of slavery’s issues and perhaps his perspective of man. In Politics, Aristotle himself questions whether a man can be destined to be a slave at birth: But is there any one thus intended by nature to be a slave . . . or rather is not all slavery a violation of nature? (1.1254a). I appreciate this last question the most. Aristotle is not a man set in his ways nor is he firmly cemented in popular thought. Aristotle felt that a man’s natural tendencies, even inherited ones, could lead him to be ruled, one who naturally was subjected. However, he did see an exception to this “natural” slavery; essentially, he qualified his own proposition because subjection might have been true for some, but not for an entire peoples and not for those who didn’t choose it. Aristotle conceded, for example, that it was unjust to enslave through war those who were not slaves by nature (1.1255a). He even termed the conquering of others for this purpose a “great evil” (7.1333b) because conquered peoples were being forced into something they weren’t born to. Aristotle did see the injustice of this single form of slavery. Could it be true? If slaves had rational minds, then they would not be natural slaves and thus, using Aristotle’s reasoning, should not be enslaved. Yet Aristotle also insisted that slavery was a natural, expected, and just foundation for a living society, for some should rule and others [should] be ruled (1.1254a). Typically, this same community required slaves, ministers of action, to function. Since they were his property, his possession, slaves were the means by which a master secured his livelihood (1.1253b). Aristotle saw slavery as just when the rule of master over slave was beneficial to both parties. He even allowed that they could share in friendship (1.1255b). Here, then, is where Aristotle concedes again that a slave might not truly be a slave by nature. They could have souls like rational men, unlike beasts of burden, since they were capable of friendship and considered part of the master (Ibid). The discrepancy lies in that they had to be rational in order to obey their masters. But if slaves had rational minds, then they would not be natural slaves and thus, using Aristotle’s reasoning, should not be enslaved. Though Aristotle clearly advocated slavery in his time, he acknowledged his opponents’ arguments, too. If slavery was a violation of nature as others had proposed, then the distinction between slave and freeman exist[ed] by law only, and not by nature and was also declared unjust (1.1253b). Since Aristotle allowed for such considerations, maybe by his generalization there couldn’t be one applicable definition for all slaves nor could there be an absolutist view of the issue. Aristotle could see that some slaves, a portion, were rational men, but he couldn’t apply that reasoning to all as a group. He could not allow for all slaves to be men, for that would destroy the infrastructure of his ideal community, the polis.  OR WHY WE SHOULD SEE LIVE PERFORMANCES. Yesterday our entire high school of 125 students and a handful of teachers saw Thornton Wilder's play Our Town at a local university, free I might add. For a play written in 1938, it is indeed a snapshot of its time approaching mid-century America post World War I and the Great Depression. After a country had seen so much loss of life and the loss of quality of life, it was no wonder that a certain hopelessness invaded the story. In essence, Wilder simplistically depicted the passing of time in the place and people of Grover's Corner, Americana. Yes, Americana. It is predictable and normal and mundane, and the characters are every bit flat and stereotypical. But that's intentional. Surely all of us can identify with the bright student, the champion baseball player, the town drunk, the mom who makes thousands of meals in her lifetime. When I asked some of my students about the performance and story, I heard some unexpected things. "Mrs. Norvell, I didn't like it. There wasn't any real hope, not in a spiritual way at least. I mean, I get the message from the cemetery people, like appreciate the present and the details in life, but it felt so hopeless. Like, do the dead people just forget everything, and that's it?" And that is why such a performance is critical. Here this young man observed, not read, that a REAL hope was absent. Here he discerned the apathy of an atheist or the absence of eternity. And I think he fairly questioned the wisdom of such lives, living without hope in God. This live performance did more than just bring life to the imagination. The experience itself brought a reality to bear because it cemented his personal belief that his choice of Christ was indeed the way, the truth, the life, not some vague hope that things would just work out. Yes, I realize that Wilder was both praising the simple life and criticizing America. I know he hoped to turn his audience to living an appreciated life, but he missed something. In 1956, the Paris Review published an interview with the Pulitzer prize winner. Wilder admitted that most of his plays and novels dealt with one or two ideas. The most dominant one was his unresting preoccupation with the surprise of the gulf between each tiny occasion of the daily life and the vast stretches of time and place in which every individual plays his role. By that I mean the absurdity of any single person’s claim to the importance of his saying, “I love!” “I suffer!” when one thinks of the background of the billions who have lived and died, who are living and dying, and presumably will live and die. Wilder was and is right. Perspective is necessary. Unselfishness is a virtue. But maybe he lost sight of the individual, the one created in God's image and the one created for eternal life, in the midst of the crowd of common men. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed