|

CELEBRATE ALL FOUR SEASONS with memoir, poetry, and short stories In the vein of Thoreau and Walden Pond, William Paul Winchester recounts his life on twenty acres in rural Oklahoma as simple and poetic. Nothing is diminutive. Embrace each blade of grass, the cow Isabel, the harvester ant, the sycamore, and the relics of the Dutchman's property. As he labored to build a house on a century-old foundation and strove to live off of the land, Winchester fully details the intricacy of each season with simplicity. Consider a summer scene—“Lightning bugs and glow worms, their bioluminescence dependent on phosphorus, were drawn to my twenty acres in such numbers that walking out on a still summer evening is like passing through the center of a meteor shower.” Winchester's memoir is just as much a commentary on contentment as it is a call to perspective. He writes, “To live in the country in a house I built for myself, with meaningful work and a margin of leisure, free to create a little universe of my own making—this was my idea of happiness.” You don’t have to be a Transcendentalist to enjoy Emerson’s delightful observations of “Earth-song.” Choose a season, and Emerson will regale you. From the “burling, dozing humble-bee” to his odes on Nature, his rambles and travels through the seasons are equally detailed in appreciation: Announced by all the trumpets of the sky, I leave you with the words of our final author, Washington Irving, and his commentary on the passing of seasons in “Christmas” from his Sketchbook-- We derive a great portion of our pleasures from the mere beauties of Nature. Our feelings sally forth and dissipate themselves over the sunny landscape, and we ‘live abroad and everywhere.’ The song of the bird, the murmur of the stream, the breathing fragrance of spring, the soft voluptuousness of summer, the golden pomp of autumn; earth with its mantle of refreshing green, and heaven with its deep delicious blue and its cloudy magnificence, all fill us with mute but exquisite delight...But in the depth of winter, when Nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn our gratifications to moral sources.” originally published November 18, 2018

0 Comments

HAVING GROWN UP IN MISSISSIPPI, I have a weakness for Southern fiction. My curiosity was especially piqued by a friend’s gift and this Southern claim. I do confess to admiring many of John Grisham’s novels, particularly Sycamore Row, but I I rarely read a bestseller unless a better-read friend attempts it first. I shun New York Times’ bestseller lists simply because they are popular. Forget the press and the hubbub. Case in point. I made the mistake of reading Gone Girl a few years ago and have always regretted the hours I lost. I found I intensely dislike amoral stories without one character to savor or cheer for. Thankfully Delia Owens’s Kya Clark is not that character, though she appears a pitiful orphan in every way. How forlorn to hear young Kya’s thoughts—“What she wondered was why no one took her with them.” Yet this read is more than character-driven. In Where the Crawdads Sing, Owens steeps her readers in a thoroughly engaging marshland setting. In fact, I would go so far as to compare her land to a living character much like Willa Cather does in her immigrant novels. The land is ripe with paradox—safe yet dangerous, shining yet muddy, life amid decay. Like Cather, Owens’s language fills us with every sensation and plants us firmly in Kya’s world of loss and hope. The land indeed nurtures her into and through her adult life with a “yearning to reach out yonder.” In her younger years, nature is a place of solace, a companion. But once her heart is awakened to human love and to the real relationship of years, creation cannot fill the void in the human heart—-- But just as her collection grew, so did her loneliness. A pain as large as her heart lived in her chest. Nothing eased it. Not the gulls, not a splendid sunset, not the rarest of shells.” And there is a void. More than a century before, Cather writes of this too. Within O Pioneers!, the land is characterized more by its strength than by its vastness. Like a human personality, it can be overbearing or supportive. Alexandra Bergson understood this. She too was intimidated at first as “the land wanted to be left alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar kind of savage beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness,” but as decades passed, the land appears an empathic friend as it “responds in kind.” More than personified, the land becomes a rounded character in full relationship with man.

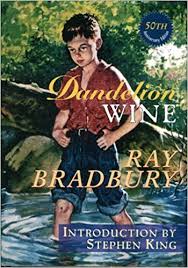

Like Alexandra Bergson, Kya possesses a faith in the land that others lack. The land is wholly human to her in relationship. And, if she has a faith, then it is no wonder that creation responds to her and reveals its treasures. It is there that she finds friendship with the marsh’s creatures, safety from prying eyes, relationship with her first love Tate, inspiration for the work of preserving nature in art. More than eco-fiction, this novel doesn't preach of preserving the marshland, at least not overwhelmingly like a smarmy salesman. The story is one of relationship. Where the land could have been seen as a trap that limits, it is ultimately a place of rescue for Kya. Photo by Timothy L Brock on Unsplash  CELEBRATE ALL FOUR SEASONS with memoir, poetry, and short stories In the vein of Thoreau and Walden Pond, William Paul Winchester recounts his life on twenty acres in rural Oklahoma as simple and poetic. Nothing is diminutive. Embrace each blade of grass, the cow Isabel, the harvester ant, the sycamore, and the relics of the Dutchman's property. As he labored to build a house on a century-old foundation and strove to live off of the land, Winchester fully details the intricacy of each season with simplicity. Consider a summer scene—“Lightning bugs and glow worms, their bioluminescence dependent on phosphorus, were drawn to my twenty acres in such numbers that walking out on a still summer evening is like passing through the center of a meteor shower.” Winchester's memoir is just as much a commentary on contentment as it is a call to perspective. He writes, “To live in the country in a house I built for myself, with meaningful work and a margin of leisure, free to create a little universe of my own making—this was my idea of happiness.” You don’t have to be a Transcendentalist to enjoy Emerson’s delightful observations of “Earth-song.” Choose a season, and Emerson will regale you. From the “burling, dozing humble-bee” to his odes on Nature, his rambles and travels through the seasons are equally detailed in appreciation: Announced by all the trumpets of the sky, I leave you with the words of our final author, Washington Irving, and his commentary on the passing of seasons in “Christmas” from his Sketchbook-- We derive a great portion of our pleasures from the mere beauties of Nature. Our feelings sally forth and dissipate themselves over the sunny landscape, and we ‘live abroad and everywhere.’ The song of the bird, the murmur of the stream, the breathing fragrance of spring, the soft voluptuousness of summer, the golden pomp of autumn; earth with its mantle of refreshing green, and heaven with its deep delicious blue and its cloudy magnificence, all fill us with mute but exquisite delight . . . But in the depth of winter, when Nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn our gratifications to moral sources.”  TWO SUMMERS AGO our back porch was inundated with carpenter bees. Their damage was disheartening, and little could be done aside from trying to kill them one by one. I offered a singular prayer. It was simple really. I asked God for help. One month later a jar of nuthatches, an entire family of extended siblings, arrived. They were a living picture. Now nuthatches or brown creepers are not common in Oklahoma, especially in neighborhoods. This little covey, however, twittered away as they began to feast, hopping through the firewood pile first, eating the young black bees. I walked as close as I could to them and told them how glad I was that they had come, that they were sent by God as my helpers. [Yes, I talk to birds, trees, and lots of God’s creation in my yard.] The group then spiraled upside down through the pine trunks, taking care of the pine bark beetles too. Within ten days all the bees were gone and so were the eleven nuthatches. Last summer a few bees returned, but I saw nary a nuthatch. I missed my friends and began to wonder if they would ever reappear. I swatted at bees with my broom instead.  This year, on the week of my wedding anniversary mind you, I was in the backyard in the heat of the afternoon looking for our cat Kiwi. I heard a single chirrup then another one a few yards away. As I peered into the trees, I saw them—two nuthatches. I moved back into the shade of the porch and watched. The smaller one, the female, was hunting along a tree trunk, but every now and then she chirped to the male who was deep in my magnolia bush. He echoed right back. Every time she moved she chirped to him as if she was sending both her location and an “all is well” signal. He always responded. My face was wet in minutes. I just knew these two were part of the family that had traveled through my backyard before, and they had returned to build a nest and a family. My home was their home. But even more, they were a living picture, a picture of working together, a reminder on my anniversary week, a picture of God's love for me, and an answer to a simple prayer once again. From the first moments when we meet Douglas Spaulding, we know his life is one of imagination and adventure. In Dandelion Wine, Doug is tantalized by the summer season, and his full-bodied experiences entice the most reticent reader to enter again into a season of discovery. One of the most notable elements of Bradbury’s fiction is this ability to depict the wonder and sometimes the harsh reality of childhood through experience and imagery. We can relive our own childhood awakening through Douglas’s first summer moments. Riding in his Dad’s car through the countryside, Doug declares that Some days were good for tasting and some for touching. And some days were good for all the senses at once. This was that day for Doug where he literally became aware of every sight, sound, and taste about him in the woods. I, too, have shared in some of those childhood experiences. I remember going on fishing trips with my father and big sister in the early Mississippi morning hours to a local pond or practically anywhere we could drive his 1971 Chevy truck under an hour’s time. Even at five or six years of age, I could bait my own hooks with crickets and worms. The problem was that I was easily distracted by the wonder of where we were. I could sit on a bank and doodle my bobber in the water for a time, but almost always, I would leave my pole and wander a dirt path or two, investigating for critters or anything I couldn’t catch in my own backyard. Some days were good for tasting and some for touching. And some days were good for all the senses at once.  For me, the freedom to explore my little unknown habitat, even for a morning, was a treasure. I could sit still and listen to the wind in the pines, the jays and their squabbles, the plunk of bullfrogs for what seemed an infinitesimal day. I could close my eyes and just feel the aliveness around me, the breeze, the humid liquid air, the sense of a twig in my hand as I dug in the dirt. Like Doug, I could then open my eyes and know that absolutely everything was there. The world, like a great iris of an even more gigantic eye, which has also just opened and stretched out to encompass everything, stared back at him. It’s the utter sense of being fully awake and being wholly part of a place and moment in time. Though Doug begins his summer declaring I want to feel all there is to feel, he soon discerns that time is slipping quickly by: The only way to keep things slow was to watch everything and do nothing. Through the experience of life and death in the town and their family, Doug and his brother realize that happy endings don’t always go with summer, but it is a part of awakening to life.  Photo by Holger Link on Unsplash Photo by Holger Link on Unsplash On one of those same summer fishing days, I remember my first experience with death, and it too, startled me. I had been fishing with a juicy worm in the hot sun without luck when I suddenly felt my bobber jerk deep. I hollered for my dad who ran to help me pull the fish in. It was a red snapping turtle instead, and it was huge to my small eyes. As fascinating as it was, it wouldn’t let go of my big worm even though my dad tried to get it to bite a stick instead. That was one aggressive turtle, and it wouldn’t let go of that line. My dad later said that the turtle had never swallowed the bait nor hook but was just plain ornery. Though I was fascinated by their tussle, my dad shouted at me to get back, then he tried again to get that turtle to grab the stick, and it did. As soon as it crunched, my dad whipped out his Bowie knife from his boot and cut off its head right where it had extended its neck. I was mortified and sickened, for I had caught many a tiny box turtle in our yard as a pet kept for weeks at a time, and I sure didn’t understand my dad’s reaction. I just sat down in the dirt and cried out of pure shock as my dad flung the parts in the lake. Like Tom who saw a different part of his mother’s character one night at the ravine or like Doug who loses a friend to a move or as both as they lose neighbors and their own great-grandma to death, so many changes come at unexpected times, and something as pleasant as a summer day can devolve into horror and grief. The wonder and simple pleasures of summer then can not only be contagious at times as we revel in creation and experience, but also tempered by the realities of life and death. originally posted 3/31/17  Brown Creeper [audubon.org] Brown Creeper [audubon.org] I LOVE OUR BACK PORCH. Sunny or rainy, I can sit outside and write all I want while I listen to the neighborhood birds and just rest in the breeze. Except for the sawdust. A few years back, I began to notice little piles of sawdust on the floor. Naturally I looked up, and to my surprise, saw perfect little holes in the cedar beams. We had bees! Carpenter bees or wood bees, they were gnawing away at dead wood, laying eggs, and letting the new larvae feast on the wood too. I researched in earnest and found out that there’s really not much you can do. Sure, fill the holes with steel wool. Ugly. Nail steel mesh to the bottom of your beams. Ugly. Install a spray system that mists every fifteen minutes to keep them at bay. Expensive. So, I did what most vigilant moms might. I prayed for the bees to go away, and I got my broom and stayed on guard several times a day for that first summer. As soon as a bee dug in, I swatted. After a few weeks, I had killed enough that further damage was averted. But this year was different. In the late spring as I sat writing, I noticed dozens of smaller, solid black bees in the woodpile. It was as if they appeared in one day. But, while I was sitting there, a bird arrived, and not one I had ever seen before. He was small and round and brown, and he didn’t mind me a bit. If a bird could appear delighted, he did. He went to town, hopping from stick to log and then diving into the pile, eating those bees. I needed to do more research. Sure enough, those all-black bees were young carpenters, and that fine bird was a Brown Creeper, a nuthatch. What an unexpected answer to prayer. I began to observe that nuthatch and his friends over the next few days, and they seemed to vacation and feast in my yard. Nuthatches never roost alone but always in a large family known as a jar. A jar of birds! The mother and father raise one brood each year, and offspring from previous years help raise the young. Siblings at your service. But I was at a loss when trying to figure out why they were so named until . . . Ascending a pine tree, his little round ball of a body turned upside down as he scaled the tree, the nuthatch moved in a spiral pecking under the bark. And then I saw it. That one moment where he caught something. I think it was a beetle. Quick as could be, he tucked that beetle under some loose bark and pounded on the bark, splitting that beetle wide open. Thus, the nuthatch, “hatching” any large insect or seed was perfectly equipped. Naturalist Winsor M. Tyler writes, “The Brown Creeper, as he hitches along the bole of a tree, looks like a fragment of the detached bark that is defying the law of gravitation by moving upward over the trunk, and as he flies off to another tree, he resembles a little dry leaf blown about by the wind.” So poetic but picture perfect. Over the next few weeks, this little community of ten happily took care of every wood bee. Tittering and chittering, they played in the dirt in the back corner of the yard and eagerly roosted in our small stand of trees. Then they were gone. The heat of summer had intensified, their food source depleted. I was sad not to see and hear them anymore. At the same time, I was filled with wonder at how God had provided for them and for me.  1938 Farm Girl, Seward, Nebraska [Library of Congress] 1938 Farm Girl, Seward, Nebraska [Library of Congress] “For the first time, perhaps, since that land emerged from the waters of geologic ages, a human face was set toward it with love and yearning. It seemed beautiful to her, rich and strong and glorious.” As she explores the life and land of her heroine Alexandra Bergson, Willa Cather creates an aura and mystique about the Nebraskan land itself in O Pioneers!. The land alone is fierce, ugly, sombre, even magical, but most significantly, it is dynamically alive. At first, Cather constructs a setting where the land appears as a separate woebegone entity: “the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness.” In its singularity, the land has doubtless endured without man. Cather describes it as a fact in itself “which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes.” Specifically, Cather relates how Alexandra’s father, “John Bergson had made but little impression upon the wild land he had come to tame. It was still a wild thing that had its ugly moods.” Yet the hardness of this pioneering life, the hardness of the land itself, did not overcome John Bergson. Emil asks his sister Alexandra, “Father had a hard fight here, didn’t he?” And she responded, “Yes, and he died in a dark time. Still, he had hope. He believed in the land.” This persistent belief and interaction distinguishes the land even further. As Alexandra and others engage and hope in the land, it responds in kind—“For the first time, perhaps, since that land emerged from the waters of geologic ages, a human face was set toward it with love and yearning. It seemed beautiful to her, rich and strong and glorious.” The land affects Alexandra’s heart and spirit, and Cather alludes to the influence of God the creator, “the Genius of the Divide,” who is part of this burgeoning relationship. Cather clearly portrays Alexandra’s connection. As Cather depicts Alexandra’s vast and fruitful property, she reveals that it is “in the soil she expresses herself best.” Although Alexandra recognized her tie to the land, she ironically doesn’t want her brother Emil to share the same connection. She clearly expresses her demand, that he must never buy land or work the land, so that he could pursue life in freedom, in choice, unlike herself. Out of her father’s children there was one who was fit to cope with the world, who had not been tied to the plow, and who had a personality apart from the soil. And that, she reflected, was what she had worked for. She felt well satisfied with her life. Perhaps Alexandra felt that her tie to the land was more than an anchor, that it instead was a trap. She felt confined to her farm and the land, as did her older brothers. More than ever, the land tends to reflect not only the mood, but now the waning hopes of Alexandra. For her, the land is simply no longer a place of goodness and freedom. As time passes, Alexandra expresses a fatalism about the land, partly due to her experiences. After Emil and Marie are murdered, Alexandra grieves for months and becomes weary of life. Here returns her “old illusion of her girlhood, of being lifted and carried lightly by some one very strong . . . she knew at last for whom it was she had waited, and where he could carry her.” By description and inference, her lover appears to be the land in human form, for that is where she will be returned in death when he carries her away “one day to receive hearts like Alexandra’s into its bosom.” Once Carl returns and pledges himself in marriage, Alexandra confirms that her commitment to Carl would lessen her tie to the land. In the same fatalistic manner, Alexandra and Carl speak of how the land has taken the best of them with the deaths of Emil and Marie. Carl states that he felt “my blood go quicker . . . an acceleration of life” when he had been with them. Maybe the land was jealous of their lives, of how others felt alive around them, for they remember an account about the graveyard, about “the old story writing itself over. Only it is we who write it, with the best we have.” Both Carl and Alexandra appear reconciled with the outcome, as if the land is fed with the death of their best. Regardless of her grief and even change in circumstances, Alexandra is yet united with the land—“‘There is great peace here . . . and freedom,’ she tells Carl. ‘You belong to the land,’ Carl murmured, ‘as you have always said. Now more than ever.’” Alexandra remains a stalwart reflection of the land as it becomes part of her—“We come and go, but the land is always here. And the people who love it and understand it are the people who own it—for a little while.”  IN MY ANTONIA, WILLA CATHER'S PORTRAYAL OF THE LAND is blurred by its intercourse with character. Not only can the land be place, but it can also be soul, an emotional center for more than one character. For narrator Jim Burden, both Antonia and the Nebraskan landscape become a place of returning, equal with the past, yet most essentially a place known as home. The land is part of Jim Burden from his earliest memories, ones that indeed he returns to. When Jim first travels to Nebraska, his young mind is captured by the vast land, “There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.” Once he arrives at his grandparents’ farm and begins to explore the property and gardens, Jim realizes a peace and comfort there—“I was something that lay under the sun and felt it, like the pumpkins, and I did not want to be anything more. I was entirely happy. Perhaps we feel like that when we die and become a part of something entire.” More importantly, as Jim’s friendship with Antonia develops, their mutual experiences across the prairie tie them together, whether exploring for gophers and earth-owls or gathering insects. “How many an afternoon Antonia and I have trailed along the prairie under that magnificence!” Yet as seasons pass and they grow older, Jim pulls away from the land as he attends university while Antonia detaches herself for a short time as a hired girl. Their similarity ends there though. Jim’s distance from the land becomes permanent whereas a disgraced Antonia returns to the land to raise her daughter after the fiasco of a promised marriage. Though she could have abandoned her childhood foundation, she chooses a limited life. In a sense, the land becomes both a rescue and a jail, for though she has a livelihood, she has chosen a life without freedom where people gossip and judge and the land feels removed. "the old pull of the earth" Yet as she explains her choice to Jim, Antonia declares, “I like to be where I know every stack and tree, and where all the ground is friendly. I want to live and die here.” Here, Jim relates how he wishes he were a boy again where he “felt the old pull of the earth” and “that my [his] way could end here,” so that he could be part of both the land and Antonia’s life. Jim knows that he could have chosen to remain even though he doesn’t. For some reason, he sees the land as part of a past sense, not his present life. In a reassuring farewell, Antonia most clearly reveals the land’s ties, that Jim will always be with her just like her dead father because of what they experienced on this enigmatic parcel of earth. Her sentiments even echo Jim’s from long ago, the day he confessed to Antonia that he felt her father’s spirit “among the woods and fields that were so dear to him.” In their final reunion, we see how Jim’s return home is a return to the land and to Antonia. Through the final chapter, Jim vividly depicts Antonia as full of the “fire of life” and a “rich mine of life, like the founders of early races.” She is the one he could tell anything to, the soul mate, the “closest, realest face,” that sees him for who he is. Antonia has become an ideal for Jim, one that is reminiscent of not just the pioneers, but of something more ancient. She is a tie to a nourishing land, a place that through time has brought healing and life to Antonia, her progeny, and finally, Jim. Jim Burden in fact launched his narrative with this same conclusion—“this girl seemed to mean to us the country, the conditions, the whole adventure of our childhood.”  credit: Audubon.org credit: Audubon.org "HE HITCHES ALONG THE BOLE OF THE TREE." I love our back porch. Sunny or rainy, I can sit outside and write all I want while I listen to the neighborhood birds and just rest in the breeze. Except for the sawdust. A few years back, I began to notice little piles of sawdust on the floor. Naturally I looked up, and to my surprise, saw perfect little holes in the cedar beams. We had bees! Carpenter bees or wood bees, they were gnawing away at dead wood, laying eggs, and letting the new larvae feast on the wood too. I researched in earnest and found out that there’s really not much you can do. Sure, fill the holes with steel wool. Ugly. Nail steel mesh to the bottom of your beams. Ugly. Install a spray system that mists every fifteen minutes to keep them at bay. Expensive. So, I did what most vigilant moms might. I prayed for the bees to go away, and I got my broom and stayed on guard several times a day for that first summer. As soon as a bee dug in, I swatted. After a few weeks, I had killed enough that further damage was averted. But this year was different. In the late spring as I sat writing, I noticed dozens of smaller, solid black bees in the woodpile. It was as if they appeared in one day. But, while I was sitting there, a bird arrived, and not one I had ever seen before. He was small and round and brown, and he didn’t mind me a bit. If a bird could appear delighted, he did. He went to town, hopping from stick to log and then diving into the pile, eating those bees. I needed to do more research. Sure enough, those all-black bees were young carpenters, and that fine bird was a Brown Creeper, a nuthatch. What an unexpected answer to prayer. I began to observe that nuthatch and his friends over the next few days, and they seemed to vacation and feast in my yard. Nuthatches never roost alone but always in a large family known as a jar. A jar of birds! The mother and father raise one brood each year, and offspring from previous years help raise the young. Siblings at your service. But I was at a loss when trying to figure out why they were so named until . . . Ascending a pine tree, his little round ball of a body turned upside down as he scaled the tree, the nuthatch moved in a spiral pecking under the bark. And then I saw it. That one moment where he caught something. I think it was a beetle. Quick as could be, he tucked that beetle under some loose bark and pounded on the bark, splitting that beetle wide open. Thus, the nuthatch, “hatching” any large insect or seed was perfectly equipped. Naturalist Winsor M. Tyler writes, “The Brown Creeper, as he hitches along the bole of a tree, looks like a fragment of the detached bark that is defying the law of gravitation by moving upward over the trunk, and as he flies off to another tree, he resembles a little dry leaf blown about by the wind.” So poetic but picture perfect. Over the next few weeks, this little community of ten happily took care of every wood bee. Tittering and chittering, they played in the dirt in the back corner of the yard and eagerly roosted in our small stand of trees. Then they were gone. The heat of summer had intensified, their food source depleted. I was sad not to see and hear them anymore. At the same time, I was filled with wonder at how God had provided for them and for me. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed