|

No other author has so immediately affected my perspective on work as Josef Pieper. In my mind, work was separate from the rest of life. Working hours have always been a discrete part of my day since I took my first job as a teenager. Maybe this division is inherent to American culture and how I grew up, but in Pieper’s mind, work is part of our response to the gift of life.

Though published decades ago, German philosopher Josef Pieper’s commentaries on work, leisure, and festivity bring to light two deficits within our culture today—true community relationship and conscious introspection. His works, Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1948) and In Tune with the World: A Theory of Festivity (1965), posit not a solution to our culture’s dis-perspective, but a call to return to a meaningful and fruitful life. If we can’t recognize leisure, then our culture is endangered. But leisure is a tricky word in the twenty-first century. Is it welcoming visitors at our leisure? Is it reclining on a couch in a leisure suit? Is it being free from work demands? Is it the opposite of work? What kind of leisure is this? . . . Reading is a liberating act. It produces agency, a sense of independence and freedom of thought. This access to ideas and understanding is a most precious gift—one that is worth laboring over in pursuit of liberty. In Reading for the Long Run: Leading Struggling Students into the Reading Life, Sara Osborne explores the riches and beauty of a deep reading life, most especially the unspoken experience of acquiring virtue through story, ‘A compelling vision of the goodness of goodness,’ as Vigen Guroian says. Reading can shape who we become, which as it turns out, is every advantage to readers who struggle. Osborne is clear. Disability does not mark students as other or deficient, but rather as human, human in that we, parents and teachers, are all weak. And in Christ, that is a strength. It’s a unique equation that forms us through years of daily effort. The difficult path to the reading life produces a kind of character that is born through hardship. Both student and teacher are shaped by weakness—his manifest through the struggle to read, and mine through the struggle to teach him.” Through her personal journey as mother and educator of a son whose learning did not follow a predictable map, Osborne hospitably portrays the reality of the long road to reading. She first describes the ideal, the power of story and our ability to identify with characters, a distinctive process akin to Charlotte Mason’s idea of relationship with people and characters of the past, present, and future. Exposing young minds to plentiful rich language from every avenue is praiseworthy, but it is realistically accompanied by what Osborne calls the “unglamorous hours” of doing the work itself with a modest, oftentimes laborious, pace.

It was a simple tweet. I posted a picture from the second day of school, showing my own annotations of a C.S. Lewis essay with the caption, “Teaching students annotation means modeling my own.” To my surprise, author Stephen Chiger responded that he taught the same, most notably in his book Love & Literacy published in 2021 for Uncommon Schools, a public charter network in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Intrigued, I wanted to see if a design to foster reading and literacy in urban public schools might share some practices with classical education. The premise of the book is a true ideal: “This is what love in a literacy classroom looks like: a love for the conversation, love for the text, and love for the ideas they both spark. When that includes all students, magic happens.” I kept reading. “As I walk’d through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a Den, and I laid me down in that place to sleep; and as I slept, I dreamed a Dream. . . .” Simple metaphors work.

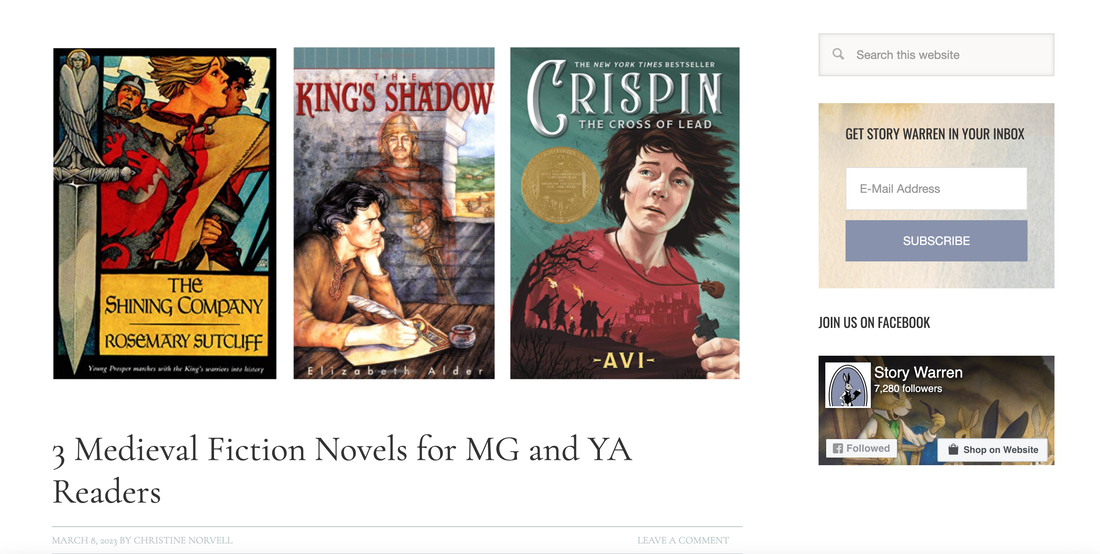

Education is a journey, Alex Sosler argues, one that cannot be separated from spiritual development because the journey itself is formation. “You have to learn who you want to be and practice being that person.” In other words, college will shape you whether you are aware of it or not. In Learning to Love: Christian Higher Education as Pilgrimage, Sosler directs students to “re-image” the potential of the years following high school because “what a student loves most has great control over the life they pursue.” And he clearly asks students to identify what they love most, even if it’s themselves. This open and frank dialogue is one of Sosler’s strengths as he introduces the history and philosophy behind Christian liberal education. A Christian liberal arts education should reflect our view of mankind with the purpose of reflecting God. These man-made institutions may be imperfect, but they do have the resources to help a student pursue the path of their soul’s formation as they learn of the true, good, and beautiful in their coursework. . . It was like watching part of some half-lost hero tale, something that belonged to an older and darker and more shining world than mine.--Rosemary Sutcliff, The Shining Company In my personal quest to find worthy reads for my middle school students, I am returning to novels published decades ago. I want my students to learn not just about peoples, places, and dates, but also to experience a time, a life, in the range of centuries known as the medieval era. I didn’t plan it, but each story happens to take place in Great Britain.

Elizabeth Alder’s The King’s Shadow (1995) is a magnificently detailed historical read for upper middle grade and young adult readers. Beginning in 1063, this living history follows the life of thirteen-year-old Briton, Evyn, during the reign of Edward the Confessor. . . Siloam Springs, AR. Centuries ago, devotion implied a commitment to God, a dedicated piety. We are devoted when we give of ourselves, to God and to others. For many of us, our devotion is an understood part of our teaching or parenting philosophy. We give time to prepare, think, plan, and collaborate to benefit our students and our children. Some call devotion “giving it your all” and see it as a standard of excellence. Others call it a virtue.

That’s how I would describe the steadfast quality in Booker Taliaferro Washington. Beginning in the 1880s, on almost every Sunday evening at Tuskegee Institute, Washington collected his students, teachers, and visitors to speak to them. The gathering wasn’t called a chapel service or a Bible study, it was simply “Sunday Evening Talks.” . . . Since we’ve moved to Siloam Springs, I’ve spent plenty of time watching my cat happily climb the old dogwood tree by our garage. Bark chips off as he climbs higher. He often looks back at me as if he wants to know whether he should jump or keep going on his elevated scratching post.

It brings to mind the wonder of tree climbing when I was a kid. I thought of trees as my friends, especially growing up in muggy Mississippi. In my mind, I can easily see a majestic magnolia with its fat arms resting on the ground. To climb under those branches, then into the cool cave of shade by its smooth trunk, was a magical experience. As a kid, I knew that tree. Yes, I climbed its branches, read in its shade, maybe I secretly carved initials or a symbol in its bark. I rubbed a leaf between my fingers and let its curved shape become a boat. I peeled off bits of bark with my fingernails, broke off a small branch to dig at a hole in the trunk. I wiped a spider web from my face and learned the sound of the wind as it hit the waxy leaves. I knew that tree. Understanding a tree begins with the experience of it as a whole and a realization that all knowledge about that tree is connected. I didn’t need a botany lesson to label things. I encountered the parts of the tree. This understanding is a central root to classical education. . . . I confess. I have asked students to make revisions to their essays. In fact, I may have casually said, “You just have some light revision work,” or “This needs heavy revision.” It sounds flippant to my ears now. Trite. But those comments all beg the same question—what does it really mean to revise our writing?

One of my former students reached out for help with a long essay. As a hopeful history major, Eric wanted to submit a college application essay on a historical subject he loved—the French Revolution. He had narrowed the topic to the role of Royalist journalists and had completed all the research, including the discovery of digitized letters and propaganda from that time period. Unfortunately, the essay had practically become a list of quotes and sources and key figures. Some connections among them had been made, but it wasn’t coherent. Yet. In the beast fables The Book of the Dun Cow and The Book of Sorrows, Walter Wangerin, Jr. crafted a living bestiary complete with a great and cosmic evil, one he carefully chose -- I discarded the notion of a human enemy, as it is in Watership Down since humans in that fantasy seemed, to me, to trouble the human reader’s ability to identify with the animals. I rejected next the notion that the enemy would arise from the animal kingdom itself since I wanted this to be evil, “das ding an sich” the thing itself rather than bad animals. Finally I hit upon the acceptable notion: that my evil would be framed in the solid, complex history of myth.[1] Thus Wangerin chose a creature that, by its nature, had always existed. The Wyrm of Old English and Old Saxon lore became a literal gargantuan worm trapped in the bowels of the earth, much like the Jörmungandr of Norse mythology. Wangerin says, “The apple has a grub in it, the earth a tapeworm.”[2]

Though many bestiaries date back a full millennium or more, the Aberdeen Bestiary from the year 1200 AD describes similar dragon-type creatures with explicit teaching. Wangerin employs the serpent of old, the medieval snake or dragon of the Aberdeen Bestiary, “a viper that pours out its poison,” a living thing that preys upon hope, spewing doubt into the minds of the creatures of the earth.[3] "Of the dragon: The dragon is bigger than all other snakes or all other living things on earth. For this reason, the Greeks call it dracon: from this is derived its Latin name draco. The Devil is like the dragon; he is the most monstrous serpent of all; he is often aroused from his cave and causes the air to shine because, emerging from the depths, he transforms himself into the angel of light and deceives the foolish with hopes of vainglory and worldly pleasure. The dragon is said to be crested, as the Devil wears the crown of the king of pride. The dragon’s strength lies not in its teeth but its tail, as the Devil, deprived of his strength, deceives with lies those whom he draws to him."[4] Wangerin’s Wyrm must tempt and deceive God’s creatures if he is ever to escape his prison, but first Wangerin introduces us to his menagerie above the earth’s crust, borrowing from Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Nun’s Priest’s Tale. Once again, I turn to preparing for the summer conference season. I've presented several workshops on poetry over the years, but for this summer, I dug a bit deeper. I asked myself, "How have I taught poetry?" In my first years of teaching high school juniors in a public high school, our American Literature textbook included the usual poets and poems—Anne Bradstreet, Phillis Wheatley, William Cullen Bryant, and so on. My classes and I dutifully read those poems aloud and lightly discussed them. I dutifully assigned the printed discussion questions in the textbook as homework. And the next day, my students turned in their dutiful attempts at answers. Duty pervaded all. We had done our part and moved on through the textbook. Duty pervaded all." When our boys were older and I returned to teaching, in a classical school this time, I heard about how teaching with passion was contagious. Well of course! I had to try it out with poetry. Trust me, my 8th and 9th grade classes were likely overwhelmed by my enthusiasm and my rousing rendition of Whitman's "O Captain, My Captain". Somehow I thought that keeping my students' attention equaled mutual enthusiasm. It did not. I next began dissecting the poems into pieces, demanding that every tiny part be labeled. Unbeknownst to me, my actions sucked out the very life of the poem at hand. I continued this process for several years and could not understand why my enthusiasm and supposed expertise did not transfer to my classes as a whole. It was not my students. I came to see that only when I happened to read C.S. Lewis's Experiment in Criticism for the first time. He writes, The literary sometimes ‘use’ poetry instead of ‘receiving’ it. They differ from the unliterary because they know very well what they are doing and are prepared to defend it. ‘Why’, they ask, ‘should I turn from a real and present experience—what the poem means to me, what happens to me when I read it—to inquiries about the poet’s intention or reconstructions, always uncertain, of what it may have meant to his contemporaries?’ There seem to be two answers. One is that the poem in my head which I make from my mistranslations of Chaucer or misunderstandings of Donne may possibly not be so good as the work Chaucer or Donne actually made. Secondly, why not have both? After enjoying what I made of it, why not go back to the text, this time looking up the hard words, puzzling out the allusions, and discovering that some metrical delights in my first experience were due to my fortunate mispronunciations, and see whether I can enjoy the poet’s poem, not necessarily instead of, but in addition to, my own one?” (151-152). I had been a thief! I had not given my students the space to delight in the poem itself. I had forced my students to use poetry.

In his Preface to Paradise Lost, Lewis says that "the old critics were quite right when they said that poetry 'instructed by delighting.'" In all my learning, in all my best intentions, I had somehow missed this step. My approach to teaching poetry in a classroom setting is quite different now, and I'm still learning. My students and I read a poem aloud and silently several times. I engage the class with questions that most resemble Charlotte Mason's narration approach. I make notes of the questions they ask me and each other. I rarely demand that my students identify parts and pieces unless the poem shouts at us to do so. I offer historical or authorial context only as their questions demand. This simplicity has created a freedom from legalistic analysis. It has given me and my students the opportunity to receive the beauty of words. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed