|

In the beast fables The Book of the Dun Cow and The Book of Sorrows, Walter Wangerin, Jr. crafted a living bestiary complete with a great and cosmic evil, one he carefully chose -- I discarded the notion of a human enemy, as it is in Watership Down since humans in that fantasy seemed, to me, to trouble the human reader’s ability to identify with the animals. I rejected next the notion that the enemy would arise from the animal kingdom itself since I wanted this to be evil, “das ding an sich” the thing itself rather than bad animals. Finally I hit upon the acceptable notion: that my evil would be framed in the solid, complex history of myth.[1] Thus Wangerin chose a creature that, by its nature, had always existed. The Wyrm of Old English and Old Saxon lore became a literal gargantuan worm trapped in the bowels of the earth, much like the Jörmungandr of Norse mythology. Wangerin says, “The apple has a grub in it, the earth a tapeworm.”[2]

Though many bestiaries date back a full millennium or more, the Aberdeen Bestiary from the year 1200 AD describes similar dragon-type creatures with explicit teaching. Wangerin employs the serpent of old, the medieval snake or dragon of the Aberdeen Bestiary, “a viper that pours out its poison,” a living thing that preys upon hope, spewing doubt into the minds of the creatures of the earth.[3] "Of the dragon: The dragon is bigger than all other snakes or all other living things on earth. For this reason, the Greeks call it dracon: from this is derived its Latin name draco. The Devil is like the dragon; he is the most monstrous serpent of all; he is often aroused from his cave and causes the air to shine because, emerging from the depths, he transforms himself into the angel of light and deceives the foolish with hopes of vainglory and worldly pleasure. The dragon is said to be crested, as the Devil wears the crown of the king of pride. The dragon’s strength lies not in its teeth but its tail, as the Devil, deprived of his strength, deceives with lies those whom he draws to him."[4] Wangerin’s Wyrm must tempt and deceive God’s creatures if he is ever to escape his prison, but first Wangerin introduces us to his menagerie above the earth’s crust, borrowing from Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Nun’s Priest’s Tale.

0 Comments

I’m no stranger to George MacDonald. In fact, I would say I often feel like his welcome companion when I’m immersed in his fiction. A Quiet Neighborhood, Castle Warlock, or Sir Gibbie are places I’ve been to, and people I’ve visited in my imagination. But MacDonald also wrote a number of essays commenting on the fairy tale genre and his own writing.

In “The Fantastic Imagination,” MacDonald clarifies that fairy tales really have nothing to do with fairies, or at least they don’t have to. They do, however, have a “natural law” unto themselves as MacDonald writes. Our imagination won’t work without it. This is what he means. When we create from our imaginations and write a story, we naturally follow a pattern of harmony. MacDonald explains it this way: If you were to give a bizarre accent to “the gracious creatures of some childlike region of Fairyland,” then wouldn’t the tale sink then and there? The pieces of the tale must harmonize and not stick out... Sometimes I reread children’s literature because I enjoy being captured again by the quality of writing and the stir of imagination. I read Laura Ingalls Wilder alongside every Louis L’Amour western in my junior high library. Not one librarian said I couldn’t read them because I was a girl, and thankfully, those same librarians pointed me next to Zane Grey. At age 13 and 14, these westerns were deep to me, even if I did recognize the plot patterns. I loved them. Action, mystery, rescue, the setting sun, the lonely West, and often, a misunderstood man.

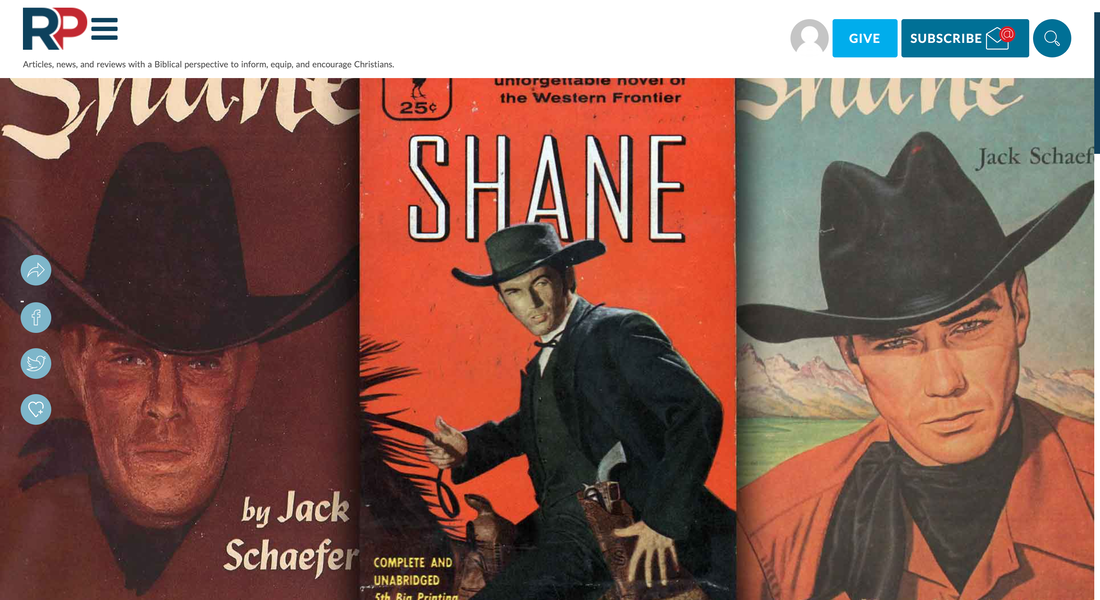

In the same vein, Jack Schaefer’s very first novel creates a story that’s even more impactful. Shane (1949) began as a short story that was serialized in three parts in Argosy magazine in the late 40s. First titled “Rider from Nowhere,” it wasn’t intended for young children, though it’s certainly suitable. Through the eyes of a child narrator and from his opening description, Schaefer crafts a deeper cowboy character than most, perhaps because we witness Shane’s moral choices and his influence upon an entire family... Every now and then I land upon a book that causes me to pause, to slow my reading. My desire to absorb what I read surpasses my desire to finish the book, even such a short one as A Confession. Leo Tolstoy was 51. Having gained fame and fortune after publishing War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877), he earnestly questioned his purpose in life. Tracing his childhood and young adult life at first, Tolstoy admits that he never thought about what he believed or why. He saw no reason to continue in the Orthodox Christianity he was brought up in. People at a certain level of education didn’t need faith, he thought. “Then as now, it was and is quite impossible to judge by a man's life and conduct whether he is a believer or not.” Tolstoy did not see how religious doctrine played a part in anyone’s life—“in intercourse with others it is never encountered, and in a man's own life he never has to reckon with it.” Instead of pursuing what he saw as an empty faith, he says, “I tried to perfect myself mentally—I studied everything I could, anything life threw in my way; I tried to perfect my will, I drew up rules I tried to follow.” His self-centered attempts soon led to wanting to appear more perfect than others. So he did whatever he wanted, and the older he grew, and the more he watched others, he knew he had to make progress. He wanted to be good but saw that he was alone in this desire. As he describes his military life, Tolstoy lists all of his sins, but as he turned to writing in his twenties, his fellow writers were no different at heart than the soldiers and officers he lived among for so long. It wasn’t long before he realized that “the superstitious belief in progress is insufficient as a guide to life. I had to know why I was doing it.” It makes me remember a phrase from long ago, “the cult of progress.” In a writer’s life today, it’s still a mantra. But then in Chapter 3, Tolstoy turns his thoughts to education as he considered plans for his own children someday. “I would say to myself: ‘What for?’” He was really asking how do we teach if we’ve never been taught-- In reality I was ever revolving round one and the same insoluble problem, which was: How to teach without knowing what to teach. In the higher spheres of literary activity I had realized that one could not teach without knowing what, for I saw that people all taught differently, and by quarreling among themselves only succeeded in hiding their ignorance from one another. But here, with peasant children, I thought to evade this difficulty by letting them learn what they liked. It amuses me now when I remember how I shuffled in trying to satisfy my desire to teach, while in the depth of my soul I knew very well that I could not teach anything needful for I did not know what was needful. After spending a year at school work I went abroad a second time to discover how to teach others while myself knowing nothing." Tolstoy clearly recognizes the voids within him. He tried to replace an absence of faith in God with a faith in himself. He tried to give himself purpose, trying to attain status and fame in the military and as a writer before turning to teaching peasant families, all before he married and had a family. His striving had left him empty, and with his retrospective, Tolstoy saw himself for what he lacked.

I’ve only read these first chapters of A Confession, and I think I’ll reread them before moving on. Maybe it’s because I’m near the same age as he was when he examined his life. Maybe it’s because, when I'm alone, I question the fruitfulness of my life. Regardless, Tolstoy gives us much to ponder. What do we truly value? Do I know what I believe? Do I know my purpose? OVER A YEAR AGO, I read Don King’s Out of My Bone: The Letters of Joy Davidman. I was struck by how quickly I felt Joy’s presence and personality in her correspondence with her sons, ex-husband, and husband-to-be, C.S. Lewis. Brash, opinionated, desperate, loving. Spanning years, these letters revealed more than a screen could. I felt who she was through her words. As one of my tutorial students and I finished discussing Pride and Prejudice this week, I was reminded of this same crystal realism. He had never read a book where letters were used so much, and he was surprised at how effective they were in fiction. As our conversation meandered, we gradually spoke of one of the most significant letters, one that Austen must have crafted with great care. As readers, we have joined Elizabeth in her misinterpretation of several characters, including Darcy. In Volume Two, Elizabeth has just rejected Darcy’s proposal of marriage and accused him of malice towards her sister Jane and towards Wickham. He then graciously extracts himself from her rudeness and sends her the longest letter of explanation the next day. It is a pivotal moment for Elizabeth and for Austen’s readers. As Elizabeth reads, we hear Darcy’s truth through his voice. In person, he speaks little in contrast to others, but here, in a letter, he is vividly present. His manners, his balance of diffidence and kindness are all revealed in his measured choice of words. We know him. I know him, and the feel of it astounds me still. But as in real life, letters can carry a sense of who a person is or was. I realize letters in literature are not new. But as in real life, letters can carry a sense of who a person is or was. Perhaps it is the deliberate time and care they take to write. My writer friend Michael De Sapio says, “It is an act every part of which expresses care, attention, and deliberate intent. It costs more, in every sense...writing a letter forces you to filter your information and set down the essential and significant. It is a true act of creation, with nothing random about it.” (Why Letter-Writing Is Essential to the Good Life)

To me, the personal creative act must be what reveals our essence, our personality in a selection of words. Whether fiction or fact, letter writing can express who we are. So how about it? I noticed lots of articles and features on writing letters at the beginning of the pandemic. I didn’t write much by hand, did you? Do you hope to? Has writing letters or reading them enriched you? Comment below or email me back. I’d love to hear more. When we think of love sonnets, most of us think of the sappy ooze of lyricists or perhaps the mush in greeting cards. But when they were first written in the 14th century, their intent was much different. OUR HISTORY It all began with Francesco Petrarch in 1304. Like his predecessor Dante, Petrarch was a devout Catholic. He too was exiled from Italy with his family due to civil unrest. Once in France, Petrarch’s father had a successful law practice, and the family prospered, so much so that he arranged the best education money could buy at the time—private tutors. By age 16, Petrarch dutifully followed in his father’s footsteps and studied law first at Montpelier then at Bologna. THE BOOKS Legend tells that since his father was supplying an allowance to Petrarch, he often made surprise visits at university. One such afternoon, Petrarch was quietly reading a book in his rented room when his father suddenly arrived. Enraged at the number of books Petrarch had purchased with his allowance, he promptly threw them out of the window and into the street below. Throwing around books at this time was no light matter. Before the printing press, many books were hand-copied and sewn together at great cost. If the story is indeed true, Petrarch likely spent a month’s allowance on one book alone. His personal library held copies of Homer’s Iliad, Cicero's Rhetoric, as well as Virgil’s Aeneid, all of which he loved dearly. FORGET THE LAW Meanwhile, his father set fire to the small stash in the middle of the street. Any passerby would know the value of that fire. Naturally disheartened, within a few months Petrarch quit law school and promptly announced he was going to be a writer and poet and take his ecclesiastical orders. Some biographers say that his father died before he could quit; others that Petrarch was simply dissatisfied with the untruthfulness of the law as a whole. A MUSE IS BORN Petrarch did pursue his minor orders as a cleric and began to write, and this is where the sonnet as a more popular form was born. Though he did not invent the sonnet, the personal and spiritual nature of his verse is intensely compelling. The story he tells lies in Sonnet 3. He was in Avignon at service on Good Friday in 1327, "the day the sun's ray had turned pale," a day of “universal woe,” when a light from the cathedral window shone on a woman rows in front of him. It was Laura de Sade, who was already wed or soon to be by most accounts. She was illumined, and a Muse was born. They likely never met or spoke from that moment, but Petrarch wrote hundreds of sonnets about her and to her. Petrarch was not selfishly obsessive, but a man instead who knew love in a different way. That God revealed her to him on Good Friday was everything. For him, Petrarch's unrequited love for Laura was about directing his soul, "From her to you comes loving thought that leads, as long as you pursue, to highest good . . ." (Sonnet 13). In his first sonnet, for example, Petrarch speaks of himself, not Laura. O you who hear within these scattered verses Petrarch does hope those who have loved before will understand his suffering. This, of course, is typical of the ideal of unrequited love sung of during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The greater the sighs, the greater the suffering, the greater the love. He may appear to be in despair, but he is actually debased, drawn to humility and repentance as he wrestles with his flesh. His spiritual state is clear—he is humbled by how he is drawn to “vanities” or his love for Laura because he knows it is not eternal, but “a quick passing dream.” From her to you comes loving thought that leads, It is God’s Love that shines from within her as Petrarch envisions Laura. With gratitude, he is drawn to a Higher Love. Petrarch seems to know that he must pursue the “highest good” or his love will become common and fleshly, “what all men desire.” Rather than wallow in despair, he is filled with hope that his Muse is leading him heavenward.

“I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it.” —C.S. Lewis I can’t explain it as well as I’d like, but there’s something to George MacDonald’s preachy style. As a teenager, I read voraciously and whipped through a number of his romances such as The Seaboard Parish (1869) and The Fisherman’s Lady (1875). In each story, a prominent character is in need of a rescue, and in a predictable pattern, MacDonald provides a devout Christian who could guide and lead the needy to Christ. Simple conflicts, happy endings, nice and neat. Yet these are only one type of novel he wrote. The fairy and fable of his early years feature deeper, even darker thoughts. Consider Phantastes (1858). Here, young Anodos, meaning pathless in Greek, discovers an atypical fairy world, a place of goodness and darkness. The inexperienced Anodos doesn’t always know who to believe among the world of fairies, trees, and creatures, and most alarmingly, he unearths his own shadow, a being that is himself and yet wholly evil. After many adventures by fable’s end, Anodos reawakens in the real world and finds he has been asleep for twenty-one days. This type of fantasy along with MacDonald’s children’s stories and poems is only one small part of his writings though. Having been a Congregational minister for a time, MacDonald can’t seem to keep himself from sermonizing, let alone moralizing, in his stories. So recently I picked up a piece of his I hadn’t read before, Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood (1866). Our story begins with the honest and friendly greeting of Harry Walton, a new vicar in a rural parish harmlessly called Marshmallows. The story is replete with stereotypical characters such as the rich old widow manipulating others through her position, the old geezer working the local grain mill, the young working-class couple separated by a gruff father, and so on. What’s unique is MacDonald’s perspective. Young Walton is ever the narrator and describes what he sees: “Why did I not use to see such people about me before?” He recognizes that he is learning to truly see each parishioner as they are, and his ideals are clear. He is driven (or is it inspired?) to make God real to the people in his charge: a man must be partaker of the Divine nature; that for a man’s work to be done thoroughly, God must come and do it first himself; that to help men, He must be what He is—man in God, God in man—visibly before their eyes, or to the hearing of their ears. So much I saw. Through Walton’s eyes and ears, we see his encounters and hear his sermons. We see his sincere desires and his need to bring people together, even if he must solve the mysteries of people themselves. He is a winning protagonist, even if pedantic in times.

Personally, I enjoyed hearing the voices of the Victorian age, whether the Spenserian carols at the vicar’s Christmas party or the pulpit pounders straight from MacDonald himself. Unlike other MacDonald novels, Scottish brogue and dialect are hugely absent since our narrator is a cultured man, all the easier for his audience to enjoy the style and theology that is MacDonald’s. Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood is available in several volumes now as a reprint or digitized for public use at projectgutenberg.com. The Wade Center at Wheaton College and the George MacDonald Society websites provide a delightful array of resources and texts. Librivox also features 19 hours of MacDonald’s Unspoken Sermons. “The truth is that nothing is less sensational than pestilence, and by reason of their very duration, great misfortunes are monotonous.” As an independent teacher, I was eager to make a curriculum shift to my World Literature class this school year. I added Albert Camus’s best-selling novel The Plague because I wondered how my students would see a fictional epidemic.

Why not use our times as a secondary context to the novel? I was not disappointed by our discussions in September. Though Oran, Algeria, is beset by plague, the novel is relatively static. It is also uniquely ahistorical. It may be set in 1947 but there are no references to World War II. Neither the Arab nor African populations of Oran are mentioned. Centuries of segregation are never described. And then there are the facts. It is not possible for a town to have sustained itself for the period of time described in the novel. Yes, the characters are realistic, but the novel is not. This unique paradigm, however, lends itself to the timelessness Camus captures. Within the bubble of Oran, Camus’s commentary as narrator allows him to describe the “portents and panic” with searing truth. As COVID broke out in March and April, The Plague, of course, was referenced and quoted repeatedly. Penguin Classics has already had to reprint it twice this year. From my class discussions, here are my top timeless quotes:

V Make me thy lyre, even as the forest is: What if my leaves are falling like its own! The tumult of thy mighty harmonies Will take from both a deep, autumnal tone, Sweet though in sadness. Be thou, Spirit fierce, My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one! Drive my dead thoughts over the universe Like wither'd leaves to quicken a new birth! And, by the incantation of this verse, Scatter, as from an unextinguish'd hearth Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind! Be through my lips to unawaken'd earth The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind, If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind? In Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind,” the wind of autumn is no longer accused of bringing a permanent death. Winter is not an evil. Yes, the seeds that the wind blows will die and be buried for but a season because the warm spring wind will certainly return to bring life. As much as I thrill to the autumn Keats describes in “To Autumn,” I find a deeper, more intense awareness in Shelley’s poem. Both poems are personal, yet Shelley’s feels like a prayer by the fifth and final stanza. With great earnestness, he asks the wind to play upon him, that he would be the harp just like the trees of the forest are strings for the wind to play upon. Shelley’s plea extends to his heart. Would that the wind could drive his dead thoughts away like nature’s seeds and bring those dead words to life. He commands the wind to do so, to scatter his words across the earth. I know, I know. Shelley may have been prompted by thoughts of glory and fame, but what if the spiritual parallel goes further? What if Shelley knew of David’s words in Psalm 49:4-5? My mouth is about to speak wisdom; my heart’s deepest thoughts will give understanding. I will listen with care to God’s parable. I will set his riddle to the music of the lyre." How unique that Shelley’s earnest determination parallels David’s. A similar passion drives them as both desire to make a mystery known through lyric.

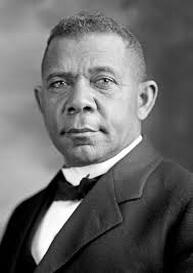

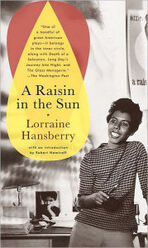

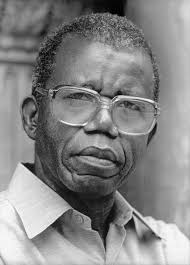

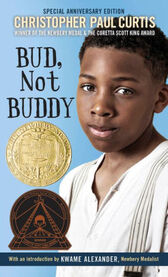

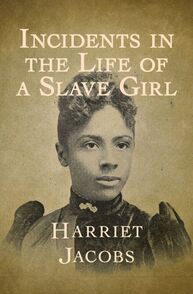

Their expressions continue to resonate with me, and my hope remains—that I too can echo Shelley’s words in prayer, “Make me thy lyre.” Spanning generations and political views, the authors I teach here have influenced how I see people, how I see my own students, and hopefully how we all see the world we live in.  1. Booker T. Washington If you read my blog, you know I’m an ardent fan of Washington and his words. [See An Educator’s Devotion and Booker T. Washington’s Compromise.] When I read his Character Training (1902) in January this year, I was inspired to be more intentional in laying excellence as a standard in my classrooms. I’ve continued to read more of his works and biographies by others, including the singular The Negro in the South lectures with W. E. B. Du Bois. It's interesting to see the two men juxtaposed. Even if you've never read these men before, Washington is naturally more positive in these lectures while Du Bois's deep sense of injustice permeates his words.  2. Lorraine Hansberry Just as Washington believed hard work and perseverance were noble efforts, Hansberry depicted a different reality in the 1950s, the limitation of the American Dream for black Americans. I know it’s not her only work, but her play A Raisin in the Sun (1957) is such a living picture. She writes to her mother, “It is a play that tells the truth about people. But above all, that we have among our miserable and downtrodden ranks people who are the very essence of human dignity.” It is the essence of a merciful humanism, a good kind, that stirs understanding in the middle of activism.  3. Chinua Achebe Like Hansberry, Achebe was published by the age of 28. I first read Achebe in college under the tutelage of a visiting professor from Nigeria. More than the class discussions about Things Fall Apart (1958), I remember the sense of my cultural ignorance. Yes, suffering, pride, and injustice are human frailties, but more than that, a native son can criticize his own country for allowing Western values to compete with traditional African culture. I also read his second novel No Longer at Ease (1960) and include my reflections here in Reading Binges. It very much reminded me of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.  4. Christopher Paul Curtis I first read Bud, Not Buddy (2000) with my oldest son when he was in third grade. Bud, a ten-year-old African American boy, runs away from his abusive foster family in Flint, Michigan. He embarks on a journey to find his father, enduring the fears and horrors of the Great Depression. Written in a strong, compelling voice, Bud, Not Buddy beautifully evokes what life was like for African Americans, especially musicians, in Michigan during the Depression. Since then, my family was captured by Curtis’s historical fiction, having read The Watsons Go To Birmingham and Elijah of Buxton. I continue to recommend Curtis to families looking for compelling historical reads.  5. Harriet Ann Jacobs At the recommendation of Karen Swallow Prior, I finally read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) two years ago. Not only had I never heard of the account, but my students hadn’t either. I now include excerpts from Jacobs after I teach Washington's Up from Slavery. Jacobs addresses her autobiography to white Northern women who fail to comprehend the evils of slavery. Published in 1861, it is a harrowing account of hiding for seven years before being reunited with her children in New York. After the Civil War, Jacobs traveled to Union-occupied parts of the South together with her daughter to organize help and begin two schools for fugitive and freed slaves. Her book was well-received in America and England. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed