CELEBRATE ALL FOUR SEASONS with memoir, poetry, and short stories In the vein of Thoreau and Walden Pond, William Paul Winchester recounts his life on twenty acres in rural Oklahoma as simple and poetic. Nothing is diminutive. Embrace each blade of grass, the cow Isabel, the harvester ant, the sycamore, and the relics of the Dutchman's property. As he labored to build a house on a century-old foundation and strove to live off of the land, Winchester fully details the intricacy of each season with simplicity. Consider a summer scene—“Lightning bugs and glow worms, their bioluminescence dependent on phosphorus, were drawn to my twenty acres in such numbers that walking out on a still summer evening is like passing through the center of a meteor shower.” Winchester's memoir is just as much a commentary on contentment as it is a call to perspective. He writes, “To live in the country in a house I built for myself, with meaningful work and a margin of leisure, free to create a little universe of my own making—this was my idea of happiness.” You don’t have to be a Transcendentalist to enjoy Emerson’s delightful observations of “Earth-song.” Choose a season, and Emerson will regale you. From the “burling, dozing humble-bee” to his odes on Nature, his rambles and travels through the seasons are equally detailed in appreciation: Announced by all the trumpets of the sky, I leave you with the words of our final author, Washington Irving, and his commentary on the passing of seasons in “Christmas” from his Sketchbook-- We derive a great portion of our pleasures from the mere beauties of Nature. Our feelings sally forth and dissipate themselves over the sunny landscape, and we ‘live abroad and everywhere.’ The song of the bird, the murmur of the stream, the breathing fragrance of spring, the soft voluptuousness of summer, the golden pomp of autumn; earth with its mantle of refreshing green, and heaven with its deep delicious blue and its cloudy magnificence, all fill us with mute but exquisite delight . . . But in the depth of winter, when Nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn our gratifications to moral sources.” V Make me thy lyre, even as the forest is: What if my leaves are falling like its own! The tumult of thy mighty harmonies Will take from both a deep, autumnal tone, Sweet though in sadness. Be thou, Spirit fierce, My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one! Drive my dead thoughts over the universe Like wither'd leaves to quicken a new birth! And, by the incantation of this verse, Scatter, as from an unextinguish'd hearth Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind! Be through my lips to unawaken'd earth The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind, If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind? In Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind,” the wind of autumn is no longer accused of bringing a permanent death. Winter is not an evil. Yes, the seeds that the wind blows will die and be buried for but a season because the warm spring wind will certainly return to bring life. As much as I thrill to the autumn Keats describes in “To Autumn,” I find a deeper, more intense awareness in Shelley’s poem. Both poems are personal, yet Shelley’s feels like a prayer by the fifth and final stanza. With great earnestness, he asks the wind to play upon him, that he would be the harp just like the trees of the forest are strings for the wind to play upon. Shelley’s plea extends to his heart. Would that the wind could drive his dead thoughts away like nature’s seeds and bring those dead words to life. He commands the wind to do so, to scatter his words across the earth. I know, I know. Shelley may have been prompted by thoughts of glory and fame, but what if the spiritual parallel goes further? What if Shelley knew of David’s words in Psalm 49:4-5? My mouth is about to speak wisdom; my heart’s deepest thoughts will give understanding. I will listen with care to God’s parable. I will set his riddle to the music of the lyre. How unique that Shelley’s earnest determination parallels David’s. A similar passion drives them as both desire to make a mystery known through lyric.

Their expressions continue to resonate with me, and my hope remains—that I too can echo Shelley’s words in prayer, “Make me thy lyre.” I FEEL LIKE I'M ALWAYS READING with plenty more to read, but I don't think I would ever describe myself as a well-read person. I have a feeling I'm not the only one too. I like reading and learning, plain and simple. I thought I'd share bits of my summer stack from last year. My stack is incomplete without my Kindle reads, but it's a fair representation. Here are my categories:  FAVORITE LIGHT READS.

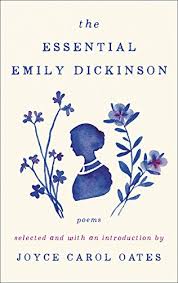

I have a privileged position. I really do. The graduating class at our small high school has only sixteen seniors this year. Most years we have fewer than thirty. Last year, I chose to add to my normal parting gift of a heartfelt note and gave each senior a pocket size poetry book. Typical frugal educator that I am, I used my Barnes and Noble coupons every few weeks and eventually purchased enough of the same five books. This year I started even earlier in the semester because I really wanted to give a meaningful volume that spoke to each student. And yes, that is quite the endeavor. Who wants to give something that will lay dust-ridden on a shelf or languish in a box of lost toys? Sorry, that’s the Island of Lost Toys. I chose these for pure readability and simple pleasure, hoping that the beauty of word choice would shine, even in the event of an obscure line or two. I could share all sixteen book choices, but that might scare you away. Instead here is the array that just might fit as you consider presents for any type of graduate.

Weary at last with way-worn wandering  4. No worthy list can ignore nature, and this is a terrible thing because I enjoy so many nature poets. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Willa Cather, Percy Shelley. It is limitless and varied. Maybe I can include two twentieth century ones then? I would choose the newest 2017 Sterling Selected Poems of Robert Frost, illustrated edition for its keepsake quality. Thomas Nason’s woodcut engravings that have accompanied several Frost volumes in decades past are included in glossy full-page contrast. The pages long to be touched. One hundred poems feature Frost and his New England at their best. Secondly I am torn between Richard Wilbur and Wendell Berry, but alas Berry has published several smaller volumes, that is “approachable” volumes, for young readers. I chose A Small Porch, which contains his Sabbath poems from 2014 and 2015 plus an extended essay on nature— The best of human work defers always to the in-forming beauty of Nature’s work . . . It is only the Christ-life, the life undying, given, received, again given, that completes our work. 5. And now for the Emilys, or is it Emmys? For Gothic verse, for sheer empathic skill in one so young, I enjoy the Everyman edition of Emily Bronte. Once again, it’s bite-sized and not as thick a tome as her complete poems. True, Bronte often deals in death and grief because it was the reality of the day, but that should not dissuade us or obscure her brighter moments. Consider "No Coward Soul Is Mine" and "Love and Friendship."

I trust these are helpful choices, and I especially would love to hear your gift suggestions. Comment on my blog or message me through my Contact page, and let's share together!  When I first wrote about how to understand poetry in the fall, I heard from so many of you. Some shared suggestions and many more requested ideas. If you missed my first article, see On Teaching My Husband Poetry. Appreciating poetry begins with finding poetry you like, poems that resonate and delight. Though he unarguably had a tumultuous life, Percy Bysshe Shelley writes in an enjoyable and, I feel, understandable way. Don’t dismiss his work because of a few “thees” and “thys.” Read through it once, then twice, to get a feel. One of the things I enjoy about Shelley’s descriptive poetry is that it is leading—he leads you to his thoughts. Poet notes. Unlike other Romantics who might get a bit lost in their creation and idealistic philosophy, Shelley is quite clear. The story goes that as he and his wife Mary, yes Mary Shelley of Frankenstein fame, were on an evening stroll in Italy in 1820, Mary commented on the evensong of the skylark, prompting Shelley’s ode. In celebration of spring, let’s look at this popular poem together. To a Skylark  Illustrated portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images Illustrated portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images So easy to hear and see and experience, And singing still dost soar, and soaring ever singest. This simple songbird is so like the Heavens he comes from that his notes are like arrows, sharp and pointed at our hearts. This expression of beauty, this skylark, is so unearthly that Shelley asks how we can know it is of the earth. What can we compare it to? He employs simple similes: a poet (himself?), a maiden, a glow-worm, a rose. Each appeals to a different perspective and physical sense. I think Shelley aspired to be as skilled with words as the skylark was with song, an experiential song of pure beauty. .Shelley then returns to a direct tone of command. He wants to know from the skylark itself, Teach us, Sprite or Bird, What sweet thoughts are thine. What are you singing of? Shelley then imagines what the bird might see before he realizes that it cannot love like a human can. That—that is something it cannot sing of, the pain or annoyance of love gone wrong. Yet maybe that is why its song is so pure.

Shelley maintains our love on earth is all the more joyful, more deep even, than what the skylark sings of because we can experience sorrow and pain. Perhaps it is the job of the poet to reveal. Consider two parts: Like a Poet hidden / In the light of thought, / Singing hymns unbidden, / Till the world is wrought / To sympathy with hopes and fears it heeded not. And Thy skill to poet were. I think Shelley aspired to be as skilled with words as the skylark was with song, a song of pure beauty. The British Library also features historical commentary on "To a Skylark." The largest library in the world, The British Library and its offerings can be found here. What if love notes or poems or sonnets weren't simply about a person? Petrarch's unrequited love for Laura was about directing his soul.  Petrarch's First Sight of Laura William Cave Thomas, 1884 Petrarch's First Sight of Laura William Cave Thomas, 1884 When we think of love sonnets, most of us think of the sappy ooze of lyricists or the flavorless mush in greeting cards. But when they were first written in the 14th century, their intent was much different. OUR HISTORY It all began with Francesco Petrarch in 1304. Like his predecessor Dante, Petrarch was a devout Catholic. He too was exiled from Italy with his family due to civil unrest. Once in France, Petrarch’s father had a successful law practice, and the family prospered, so much so that he arranged the best education money could buy at the time—private tutors. By age 16, Petrarch dutifully followed in his father’s footsteps and studied law first at Montpelier then at Bologna. THE BOOKS Legend tells that since his father was supplying an allowance to Petrarch, he often made surprise visits at university. One such afternoon, Petrarch was quietly reading a book in his rented room when his father suddenly arrived. Enraged at the number of books Petrarch had purchased with his allowance, he promptly threw them out of the window and into the street below. Now throwing around books at this time was no light matter. Before the printing press, many books were hand-copied and sewn together at great cost. If the story is indeed true, Petrarch likely spent a month’s allowance on one book alone. His personal library held copies of Homer’s Iliad, Cicero's Rhetoric, as well as Virgil’s Aeneid, all of which he loved dearly. FORGET THE LAW Meanwhile, his father set fire to the small stash in the middle of the street. Any passerby would know the value of that fire, and naturally disheartened, within a few months Petrarch quit law school and promptly announced he was going to be a writer and poet and take his ecclesiastical orders. Some biographers say that his father died before he could quit; others that Petrarch was simply dissatisfied with the untruthfulness of the law as a whole. From her to you comes loving thought that leads, as long as you pursue, to highest good Petrarch did pursue his minor orders and began to write, and this is where the sonnet as a form was born. The story he tells lies in Sonnet 3. He was in Avignon at service on Good Friday in 1327, "the day the sun's ray had turned pale," a day of “universal woe,” when a light from the cathedral window shone on a woman rows in front of him. It was Laura de Sade, who was already wed or soon to be by most accounts. She was illumined, and a Muse was born. They likely never met or spoke from that moment, but Petrarch wrote hundreds of sonnets about her and to her. NO STALKING HERE The thing is Petrarch was not some obsessive stalker, but a man instead who knew love in a different way. That God revealed her to him on Good Friday was everything. For him, Petrarch's unrequited love for Laura was about directing his soul, "From her to you comes loving thought that leads, as long as you pursue, to highest good . . ." (Sonnet 13).  No, there's no such thing as husband poetry. I mean my husband asked me to teach him more about poetry. My husband felt there were decided holes in his education, but I thought surely somewhere in junior high or high school a dedicated teacher must have taught him some famous verse. He swears he remembers nothing of the sort. Thus, three months ago, my husband picked up a volume of Emily Bronte poetry and determined to understand what he read. He was already a decided Bronte sisters' admirer, so likability wasn't an issue. What did become an issue was rhyme scheme and syllable structure. So what to do? Consult with your English teacher wife of course. As he read poetry before bed each evening, he began to ask me questions like Why does this line have eight syllables and this one has ten? I know, I know. Nerd alert. How many married couples talk like this before falling asleep? Anyway, I began by asking him not only to count syllables in every line, but to also determine if there was a pattern. How many lines are in the overall poem, sweetie? Did you say 14? So what type of poem is that? What was Bronte imitating? Pretty soon I realized we needed to start at the beginning. All the intelligent Rush lyrics of his youth bred a natural appreciation for poetry and the lyrical art, but that didn't mean he understood the required skills or genius of the poet's work. This is what we've learned so far in the poetry journey: STEP ONE: Read poetry you like, poetry you're drawn to. Each person has their own taste of course. Bronte did that for him as did Frost and Seamus Heaney. STEP TWO: Break apart the poem skeleton. This is tricky because if you spend too much time identifying parts you can also remove the pleasure of reading for the beauty of the thing. At the same time without the knowledge of parts it's hard to appreciate the whole. Think of the human skeleton. Knowing the parts of the body that frame it and allow it to stand and move increases our appreciation of its overall appearance. STEP THREE: Find a teaching text that's written at your level. Perhaps the most difficult creature to find, an instructional book is a necessary thing unless you already have an English teacher spouse at your side. From homeschooling curricula to college-level texts, there are too many choices. I've read quite a few that make poetry more difficult and even more that make it too simple. The trick is to find the one that fits you. As an adult learner, my husband didn't want a middle school beginner though he was willing. Instead we went entirely old school. Why not learn from two distinguished Yale professors? MY TOP RECOMMENDATION Understanding Poetry by Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren. It's no longer in print but is a valuable text if you find one. You can learn so much from reading just two chapters on narrative and descriptive poems. Brooks and Warren include plenty of examples AND include their commentary on how the poem works and what it means. So, so helpful to learn from their wealth of experience. Brooks also has his own poetry textbook titled The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry. Though I haven't read it yet, it comes with high reviews. And as a bonus, read Dwight Longenecker's essay "Why You Need Poetry." He provides much needed motivation for why poetry benefits our minds, ourselves, as a creative outlet.  I taste a liquor never brewed – From Tankards scooped in Pearl – Not all the Frankfort Berries Yield such an Alcohol! Inebriate of air – am I – And Debauchee of Dew – Reeling – thro' endless summer days – From inns of molten Blue – When "Landlords" turn the drunken Bee Out of the Foxglove's door – When Butterflies – renounce their "drams" – I shall but drink the more! Till Seraphs swing their snowy Hats – And Saints – to windows run – To see the little Tippler Leaning against the – Sun! As a poet, Emily Dickinson creates a buffet for the senses and the imagination in “I taste a liquor never brewed.” By her first implication, the reader knows that this poem does not refer to something natural, something “brewed” by man, but to the sense of something hard to define. This mysterious element combined with unusual imagery elicits a playful almost festive theme of the summer season. Dickinson persistently uses drunken imagery in all its connotations as a metaphor for the exhilaration she enjoys outdoors in the summer. She first mentions that nothing can compare to this heady sensation, no other emotion can “yield such an alcohol.” The imagery continues as she next mentions she is drunk on the very air and summer dew, “reeling” all season long in the “inns” or taverns under the sky. Dickinson even relishes summer more than the insects that thrive then. Lines 9 through 12 show how the bee has had his fill of “drink” from the foxgloves, and the butterflies now “renounce their drams” and can’t drink or even desire another drop. Yet Dickinson exclaims she’ll keep drinking—consuming, absorbing, enjoying all creation. So much of Dickinson’s description lies in tangible sensation. First person point of view pervades these first three stanzas, and this is part of the power of this poem. In line 1, Dickinson tastes this “liquor” of summer. In line 5, she is the one who is drunk on air and dew, and in line 12, she shouts that when the bee and butterflies are done drinking, “I shall but drink the more!” Her point of view is just that, not a commentary or guide to how the reader should feel about summer, but an exclamation of her intense emotion in a most unusual metaphor. However, the perspective of the final stanza shifts as Dickinson describes angels and saints in heaven gazing down through their “snowy Hats” or clouds and “windows” at her. As narrators, they in turn term her a “Tippler,” someone who makes a habit of drinking. Interestingly, a tippler isn’t an extreme drinker or drunk but simply a regular and daily drinker. The angels and saints witness her “Leaning against the - Sun!” not overcome and leaning against a bar or wall in a tavern, but against the sun itself, the epitome of the season. Dickinson is the one regularly “drinking in” the sun. So much of Dickinson’s description lies in tangible sensation, the taste of drink, or even physical movement, but not in color or sound. Yet the absence of these two senses does not diminish her apparent expression of heart-felt emotion. She remains wholly conjoined to the essence of summer. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed