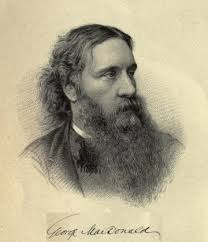

ANNALS OF A QUIET NEIGHBORHOOD “I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him. But it has not seemed to me that those who have received my books kindly take even now sufficient notice of the affiliation. Honesty drives me to emphasize it.”—C.S. Lewis I can’t explain it as well as I’d like, but there’s something to George MacDonald’s preachy style. As a teenager, I read voraciously and whipped through a number of his romances such as The Seaboard Parish (1869) and The Fisherman’s Lady (1875). In each story, a prominent character is in need of a rescue, and in a predictable pattern, MacDonald provided a devout Christian who could guide and lead the needy to Christ. Simple conflicts, happy endings, nice and neat. Yet these are only one type of novel he wrote. The fairy and fable of his early years feature deeper and darker thoughts. Consider Phantastes (1858). Here, young Anodos, meaning pathless in Greek, discovers an atypical fairy world, a place of goodness and darkness. The inexperienced Anodos doesn’t always know who to believe among the world of fairies, trees, and creatures, and most alarmingly, he unearths his own shadow, a being that is himself and yet wholly evil. After many adventures by fable’s end, Anodos reawakens in the real world and finds he has been asleep for twenty-one days. This type of fantasy along with his children’s stories and poems is only one small part of his writings. Having been a Congregational minister for a time and a devout Christian, MacDonald can’t seem to keep himself from sermonizing, let alone moralizing, in his stories. So recently, I picked up a piece of his I hadn’t read before, Annals of a Quiet Neighborhood (1866). Our story begins with the honest and friendly greeting of Harry Walton, a new vicar in a rural parish harmlessly called Marshmallows. The story is replete with stereotypical characters such as the rich old widow manipulating others through her position, the old geezer working the local grain mill, the young working-class couple separated by a gruff father, and so on. What’s unique is MacDonald’s perspective. Young Walton is ever the narrator and describes what he sees: “Why did I not use to see such people about me before?” (99). He recognizes that he is learning to truly see each parishioner as they are, and his ideals are clear. He is driven (or is it inspired?) to make God real to the people in his charge: “a man must be partaker of the Divine nature; that for a man’s work to be done thoroughly, God must come and do it first himself; that to help men, He must be what He is—man in God, God in man—visibly before their eyes, or to the hearing of their ears. So much I saw” (137). Through Walton’s eyes and ears, we see his encounters and hear his sermons. We see his sincere desires and his need to bring people together, even if he must solve the mysteries of people themselves. He is a winning protagonist, even if pedantic at times. Personally, I enjoyed hearing the voices of the Victorian age, whether the Spenserian carols at the vicar’s Christmas party or the pulpit pounders straight from MacDonald himself. Unlike other MacDonald novels, Scottish brogue and dialect are hugely absent since our narrator is a cultured man. All the easier for his audience to enjoy the style and theology that is MacDonald’s. It’s available in several volumes now as a reprint or digitized for public use at projectgutenberg.com. Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed